NEWS 2009

Guest Lecture: James McAllister On Beauty in the Sciences

November 15, 2009

David Duncan (PY '10, USA)

On Thursday, November 5th, James W. McAllister, associate professor in Philosophy at the University of Leiden and author of Beauty & Revolution in Science, gave a spirited lecture on the unusual topic of the relationship between beauty and truth in science. Dr. McAllister's lecture tied into the core course for PY students on Objectivity. In addition to the assembled project year students and instructor Bruno Macaes, Co-Dean Peter Hajnal and faculty member Catherine Toal were also present.

Dr. McAllister sketched out a brief but elegant argument with the provocative starting point: "Is beauty a sign of truth in science?" Dr. McAllister quickly moved to define his terms, dividing the consideration of beauty in science into two broad categories; projectivism and objectivism. As the names suggest, the objectivist position maintains that beauty is an objective and measurable property of theories, while the projectivist position suggests that the aesthetic value of a theory is the result of projection onto theories by the relevant scientific community that considers them. McAllister took a projectivist position, defining beauty as in motion and evolving over time. Radical, paradigm shifting theories are usually regarded as ugly, and as they build a track-record of empirical success, they begin to be perceived as more beautiful.

On Dr. McAllister's account, the most pressing issue from the perspective of utility concerns the question: "Is beauty linked to the truth, validity, adequacy, or effectiveness of theories?" His answer was that an a priori link seems unlikely because, empirically and historically speaking; there is an incredible diversity of responses. Furthermore, it is not really possible to substantiate the claim that there is something distinct from, but necessarily linked with, truth. Instead, his hypothesis was one of aesthetic induction, where aesthetic preferences evolve in response to empirical performance. Therefore, the relationship between beauty and truth in science is established inductively in an a posteriori manner and is "perfectly reliable" for as long as the present scientific paradigm happens to endure.

During the presentation, students and faculty were able to ask questions of Dr. McAllister. Some questions were merely requests for clarification while others represented serious challenges to his hypothesis. McAllister also participated in the seminar that followed the presentation and defended his position further, particularly against the suggestion that the definition of beauty as applied to science is so distinct from how beauty is conventionally defined in the humanities that it is not meaningful to use the same word for both concepts. The discussion went on for approximately two hours and was intellectually intense but amiable throughout. As 4:45 rolled around all too quickly and class was adjourned, Bruno thanked Professor McAllister for his presentation and thoughtful participation in ECLA's classroom methodology.

Behind spiritual values: Cathedral tour during Harz trip

November 7, 2009

María Cruz (AY '10, Argentina)

As part of ECLA's trip to the Harz Mountains students and faculty visited two medieval cathedrals, one at the beginning and one at the end of the trip. They were both built in the same period, and both were in the gothic architectural style. Yet each had particular details which made it unique and which connected it to the history of its home city.

It is possible to identify at quite a distance a cathedral built during the gothic period. The first thing that jumps to the visitors' eyes is the amazing height to which such a building reaches. The sharp towers seem to attempt to scratch the furthest clouds. These pointed structures recur throughout the structure of the building, both inside and outside. On entering the building, one can't but feel small facing such architectural magnitude. Large windows cut through the wall every few metres, close to the ceiling of the church. Geoff Lehman, the ECLA faculty member who guided the tour through these medieval buildings, pointed out that the large high-window style was enabled by new technical discoveries and were designed to convey a spiritual message: "having such large windows, so close to one another, is possible because the building is supported not only from the inside, but also with buttresses on the walls outside. Before this, they needed very strong walls and couldn't structurally afford the delicate window features; otherwise the roof would have fallen in". The light flooding through these huge openings also had a very strong meaning, intended to represent the light sent by God to the world. The impressive height of the buildings is intended not only as symbol of divine greatness, but as a clear attempt to build a monument reaching toward the heavens.

The first Cathedral we visited was Magdeburg Cathedral, dedicated to St. Maurice and St. Catherine. Otto the Great commissioned this magnificent work in 955. Due to the devastating city fire of 1207, the Cathedral had to be rebuilt, a process that started in 1209 and took 300 years. The completion wasn't achieved until 1520, and it was with this rebuilding - commissioned by the Archbishop Albrecht II von Kefernburg - that the Cathedral gained its impressive dimensions. Only a wall remains of the original building. Motifs from the natural world are a dominant iconic presence throughout its extent. At the very entrance, the doorknob has the shape of a bird, that, when turned to open the door, leans forward to feed three young pigeons. Most of the intersections of pillars and roof are decorated with ornate leaf patterns that also appear in branches several times across the wall sculptures. Furthermore, the traditional gothic ribs that cross the ceiling bear different nature-inspired figures in the intersections: flowers and wolves, among others. The inside pillars merge into the ceiling with an organic shape, resembling trees. The whole environment leaves the visitor with a peaceful feeling, a very strong idea that the spiritual search and religious life are deeply rooted in nature, man's most basic habitat.

The Cathedral of Halberstadt, the second one we visited, is dedicated to St. Stephan and St. Sixtus, and was built from 1236 to 1486. The Diocese of Halberstadt, one of the most important of the empire, lasted from 804 until 1648. It is world famous for its treasury: more than 600 works of art from the Middle Ages are still preserved there today. The impressive collection consists of altarpieces, sculptures, manuscripts, furniture, works of bronze and gold, which have been on display in the Halberstadt Cathedral since April 2008.The architecture of this Cathedral is a distinctive example of French Gothic, unlike Magdeburg's, which appeared more solid and had an austere simplicity. Halberstadt Cathedral is in a certain sense more refined in this way. It also has a very different iconography. Inside, the large windows of the building, unlike Magdeburg's, serve a didactic function: they are crowded with colorful representations of some of the Bible's most famous passages. The building itself is much smaller when compared with the Cathedral at Magdeburg, although it too reaches staggering heights. The arcs on the ceiling at Haberstadt were intersected with different coats of arms, probably those belonging to the most important families of the city.

Overall, it was certainly enlightening to visit both Cathedrals and to gain insight into the specific styles of each monument by means of comparison. Even though they were built around the same period, and both are unambiguous examples of the French Gothic architectural style, it suddenly becomes very clear how very different effects can emerge within the same style of devotional aesthetic.

Trip to the Mines of Rammelsberg

November 1, 2009

David Duncan (PY '10, USA)

During the weekend excursion to the Harz Mountains, a group of ECLA students led by faculty member Dirk Deichfuss visited the Mines of Rammelsberg nestled in the town of Goslar. The mines are impressive both from a technical and historical perspective, having been in continuous operation for over a thousand years, and reaching a depth of 400 meters. The mines of Rammelsberg are now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Students were greeted by a tour guide with the traditional miners greeting "Glückauf!" wishing us a safe descent into and return from the mine. We were then directed to the old changing area where hardhats were distributed. Before embarking on our descent into the mines themselves our guide gave a brief description of the ore distribution of the Rammelsberg site. As she explained, the mines are particularly unusual for two reasons. Firstly, because of the high percentage of valuable minerals: up to thirty percent silver, copper, zinc, lead and other metals per load of excavated material. Secondly, because of the distribution of deposits discovered in a grid-like shape for hundreds of meters down, rather than in the vein structure found in most mines. The wealth of silver deposits, initially accessible from the surface, was what led The Holy Roman Emperor Henry I to officially found Goslar as a Free Imperial City. The two rare features, deep deposits and high purity, are what allowed the Rammelsberg mines to be economically viable for over a millennium. Also of interest was a scale model of one of the water-powered wooden wheels used to draw the ore up from the depths of the mine from medieval times through to the beginning of the 20th century.

The group then walked partway up a hill to the doors of the mine entrance, which for all of its history was unassuming but very sturdy. We went through a long underground corridor that at times was less than two meters high. Although this forced a few of the taller members of the group to stoop on occasion, for the most part the mine was surprisingly spacious, with wide corridors and large open areas. In one such area, we saw a full-size, fully functional waterwheel, the size of which was all the more impressive because it had been brought into the mine piece by piece and re-assembled by the pale light of gas lamps!

As we descended deeper into the mine, the group viewed two more waterwheels and a large space where one of the previous wheels had historically stood. Along the way we viewed an underground mock-up that demonstrated how the laying of fire was used by engineers to mine ore in a delicate process that required the evacuation of the mines and precise control of airflow entering the mine.

As we travelled up approximately 40 meters of narrow metal steps to exit the mine, we were able to see the ladders, originally wooden and then later iron, that miners had to make use of when leaving work up until the 20th century. As miners would often be hundreds of meters down, travelling up the ladders could take more than an hour and on average there were one or two deaths each year from falling. This fact must be reckoned alongside the knowledge that, during most of its history, the mines never had more than about two hundred workers.

While everyone enjoyed the tour, by the time we emerged from the darkness of the mine there was a sense relief at being aboveground again. We thanked our tour guide and walked back to the youth hostel, much more appreciative of the engineering expertise and physical determination that had built the Mines of Rammelsberg and the town of Goslar.

Walk to Brocken Mountain

October 23, 2009

María Cruz (AY '10, Argentina)

After three weeks of intensive academic activities, most of the ECLA community embarked on a three-day excursion to the Harz region that began early on Friday, October 23. First stop was Magdeburg, a small city by the Elbe River with quite a number of interesting examples of medieval architecture, as well as more modern buildings. Here faculty and students visited the Magdeburg Cathedral, an impressive gothic structure that dates back to 955 AD.

By the afternoon, the group reached the historic city of Goslar - our final destination. The first activities involved exploring the picturesque town centre, which looked as though it had stepped out of a history book. The settlement at Goslar was founded in 922 and only a hundred years later became an Imperial City, one of the most important of the Holy Roman Empire. Famous for the Rammelsberg Ore Mine, both this and Goslar's Old Town were declared World Cultural Heritage Sites by UNESCO in 1992.

One of the most thrilling experiences took place on Saturday when faculty and students set out to Brocken, a mountain 1142 meters high and the highest peak of the Harz region. The long hike took around six hours to the top and back. Since the weather was warm and sunny, the undertaking on the whole was both fun and challenging. At the beginning, there was only a path through the thick forest, a great view that every now and then offered wooden bridges over streams and landings to rest from long hours of walking. The path turned out to be more and more difficult as we climbed towards the peak since about half the way up we encountered snow. People of all ages and diverse origins were taking the same tour, giving the experience a truly communal feeling.

Closer to the top, the path ran alongside railway tracks and every fifteen minutes or so a black and red fairytale train with steam popping out of its chimney would make its way past. The Brockenbahn, built in 1899, is one of the three metre gauge railways that run across the Harz National Park. It is certainly a big attraction for those who want to know the Harz region but aren't tempted by the long hours of walking.

Brockenbahnof, the highest narrow railway station in Germany, served as a military base for border surveillance during the Cold War. Until the Berlin Wall fell, the mountain was off limits to all but the Soviet army. For both local inhabitants and visitors alike, the opportunity to hike through the park signifies a celebration of complete freedom.

Once on ground zero again, the ECLA troupe gathered in a warm place to share views on the experience while sipping hot chocolate.

The Installation Exhibition: A sonic experience

October 21, 2009

María Cruz (AY '10, Argentina)

Screaming babies, dark hallways, heartbeats, water, broken TVs, shouts and singers. The first exhibition for the installation module that took place on Wednesday October 21 filled the air with a medley of different sounds that moved the visitors emotionally through the provocation of contrasting moods.

The tour consisted of eight different studios, each presenting a different environment created by a single student. The aim was to express a particular idea or feeling in an artistic way through sound engineering. With the help of lights, cloth, strings, newspapers and other materials, the students were able to submerge the guests in an alternate experience. Picture going through a door to a dimly lit room, covered with torn black fabric, and containing a human size black bag, and filled with sounds of screaming, shots, running, breathing, a shot, and then silence. Another room demanded that visitors concentrate on an ancient book while hearing the sounds of a baby crying, a toilet flushing, and voices carrying through what appeared to be very thin walls.

The exhibition had been announced at the beginning of the week to eager students and faculty who were already anticipating the event: it takes place every year as part of one of ECLA's most popular elective courses. Wednesday's was only the first of the four installation showings to occur this term, which means the best may well be yet to come. Future installations will focus on light, video, and the final work is expected to combine all three.

Former installation students who have had the opportunity to be involved in previous years at ECLA have stated that going through this process is a unique experience. Since the raw material comes from the students themselves, working with it to create an installation often entails a process of self-discovery which involves seeking to meet the challenge of communicating one's ideas to others. In the module tutor David Levine's own words: "it's about discovering and using your own language to express something that is important to you".

The showings, that took place from 7.30 pm to 8.30 pm, certainly triggered a great deal of nervous excitement in each of the eight students. Their work was to be exposed to the assessment of their peers. Now that this first experience has passed by, the artistically-driven students of the ECLA installation module have some exciting projects ahead. We look forward to the next exhibition, scheduled to take place in week 5.

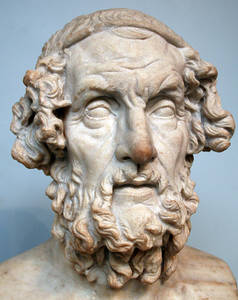

- Marble portrait bust of Homer at The British Museum

Poetry Night

October 2, 2009

Diana Martin (AY '10, Romania)

Continuing the Berlin Weekend programme, on Friday night we gathered at ECLA faculty member David Hayes' apartment to share our favourite poems both in translation and in the original. Sitting on chairs or on the floor, we let our poems flow in circles, immersing ourselves in the mysteries of language.

The night was opened by Robyn Mayer, who recited Hendrik Marsman's poem Herinnering aan Holland / Memory of Holland. The poem represents an emotional description of Robyn's country, a "limitless low-lying land where the sky hangs low and in grey vapours of colour, the sun is slowly blurred".

The poem chosen by Luzie Meyer, Hälfte des Lebens / Half of Life by Friedrich Hölderlin, was a celebration of exuberance and spectacular beauty, while Anna Csak introduced us to the despair and lack of hope of Attila J zsef, a poet less known outside Hungary. The poem chosen by Anna is entitled Születésnapomra / For My Birthday and offers a bitter take on Attila J zsef's troubled life. "Gimcrack knickknack [...] The thirty two are gone, and heck, I've never earned a monthly check".

Luisa Tolu decided to present Antoine Cassar, a Maltese poet who explores the way in which words from various languages can be combined in order to create powerful and exotic sounding poems with a fluid rhythm. His background as a translator allows Antoine Cassar to write his mosaic-like poems not only in his mother tongue, but also in English, Spanish, Italian and French. Luisa revealed his special style with the poem Nota Bene: "The skies are cold and bleak, passo appresso passo mi pento e mi rinvio, nuit d'orage, cri sauvage".

Dialog interior / Interior Dialogue, the poem that I recited, invokes "the grand silence that is necessary in order for any dialogue with one's own self to become possible". It is a poem full of plastic images and mystery, born from the imagination of the surrealist painter Victor Brauner.

The readings closed with the lines of Mark Halliday, as David Hayes recited the poem The Boiling Water. All of us gathered there could identify with Halliday's words in respect to the year at ECLA about to begin: "Serious for us that we met..."

At the beginning of every academic year, and also during the summer school, students and faculty gather to learn more about the special features of each other's cultures, ranging from literature to gastronomy. This ability to create a place where we can inspire one another through shared exploration of our various backgrounds is one of ECLA's cherished traits.

Visit to Martin-Gropius-Bau. "Bauhaus. A conceptual Model"

October 2, 2009

María Cruz (AY '10, Argentina)

In spite of the fact that it was first developed ninety years ago, and that the art school only existed for fourteen years, Bauhaus never gets old. There is always something new to discuss about one of the greatest schools of modernity. As part of the Berlin Weekend program, on Friday October 2, a group of students from the European College of Liberal Arts visited the Martin Gropius Bau on the occasion of the exhibition "Bauhaus. A Conceptual Model."

The exhibition was laid out in eighteen different galleries, organized in chronological order, each one of them representing a different period in the history of the Walter Gropius School of Design and Architecture. The first stage of the tour frames the birth of Bauhaus, giving information on the social situation that obtained in the early 1900s. At the end of this stage there was a video of Gropius himself explaining how he changed his conception of art in order to respond to the social changes occurring at that time.

Unlike other exhibitions on Bauhaus, which have tended to focus on one particular period of the school, this one was structured in order to provide a clear view of the engagement with modernity that the school undertook. The exhibition proceeds all the way through galleries such as "Art-inspired impulses", "The Bauhaus Masters", "The Student's Free Art", "Elementary and Constructive", "The teaching of Kandinsky, Klee and Moholly-Nagy", to "De Stijl and Constructivism" and "The 1923 Exhibition", to name just a few. The visitors could then see the most important issues that the architecture school dealt with. As stated by the organizers: "The exhibition Bauhaus. A Conceptual Model centers on the comprehensive significance of the Bauhaus for the development and internationalization of modernity and goes beyond, examining its world-wide, lasting impact on architecture and design up until the present day". The relevance of the exhibition extends well beyond the Bauhaus movement itself, displaying the enduring influence of Bauhaus throughout subsequent decades.

Bauhaus is commonly known for its workshops, the art-studio class format, and also for its concise and practical view of design. But the exhibition didn't only show the most popular aspects of Bauhaus. The last galleries were dedicated to lesser known themes such as "The Organization of Life Processes"; "People's Necessities, not Luxuries"; "Photography at the Bauhaus" and "Intentional Time Captured in Space".

While all these galleries were around the hall, the center bore two very intriguing pieces. One of them was the Installation "Do-it-yourself-Bauhaus", by the American artist Christine Hill, which focused on the trivialization of Bauhaus in today's consumer and every-day culture. The other piece was a video installation by Ilka and Andreas Ruby, "Endless Bauhaus", where ten interviewees expressed their opinion about the meaning of Bauhaus ideas today.

Designed by the scenographers Chezweitz & Roseapple, "Bauhaus. A conceptual model" was presented in collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This exhibition, with well over 900 pieces, constitutes the largest Bauhaus exhibition in history. From the viewpoint of a liberal arts student, it was very enriching to appreciate - in an holistic way - this major contribution to the history of art and design.

ISU 2009 GUEST LECTURE: Ira Katznelson on Toleration

August 3, 2009

Nora Georgieva (ISU 2009, Bulgaria)

"However flawed toleration may be, a decent human life would not be possible without it. And it is most needed in situations when it's difficult to achieve," Dr. Ira Katznelson said during his lecture at ECLA on July 27.

Author of many books and publications, former president of the American Political Science Association and of the Social Science History Association, Dr. Katznelson is currently a professor within the History and Political Science Departments at Columbia University, where he has taught for the past 15 years. At ECLA he gave an engaging and structured presentation on the topic "What is Toleration? Reflections on the Civil Membership and the Western Liberal Tradition." The definition of toleration offered by Dr. Katznelson for the purpose of his lecture was "an act of reflective and deliberate not-doing against those you dislike even if you posses the means to do so." We appreciated his comprehensive approach to the topic, as he drew a link between several of the texts we read in the past three weeks, toleration and cruelty, the topic of focus during Week 4.

His main contention was that toleration and liberalism enhance one another, but that it is too dogmatic to think this connection is obvious and indisputable. To support his argument, Dr. Katznelson discussed the main principles of liberalism and pointed out difficulties in completely reconciling it with toleration. For example, liberalism supports the rights of the individual, but tolerance emphasizes the need to set boundaries which may limit certain rights.

This was Dr. Katznelson's first visit to ECLA. "I'm quite interested in the nature of liberal arts education generally and therefore the kind of experiment ECLA represents, a small, intensive, multinational education focused on questions of values and reading great texts. [I think] this is a successful format of education," he said.

Liberal arts education plays a role in promoting toleration but it's not sufficient, Dr. Katznelson said. While this type of education enhances appreciation for human diversity and forces us to think hard about our assumptions, it alone gives no guarantees. At least equally important is the existence of institutional arrangements that give scope to diverse ways of living because one person at a time is not enough to create a setting of toleration. Human history gives examples of people who were educated in the liberal-arts tradition but did not practice toleration. "A good liberal arts education forces individuals out of their zone of comfort and asks them to understand a wide range of experiences, cultures, practices. Hopefully that makes toleration more likely. I think it does," Dr. Katznelson said.

We hope Dr. Katznelson will return to ECLA and were happy to hear that he enjoyed his time with us as well: "I've been treated with warmth, hospitality and intellectual engagement. Even though I've been here a short time, it was extremely interesting to me," he said.

SPEECH NIGHT AT ECLA

July 29, 2009

Nora Georgieva (ISU 2009, Bulgaria)

After almost three weeks of philosophizing in the company of Montaigne, Seneca, Tolstoy, Machiavelli, Shakespeare and other great minds, we were ready to take on another challenge - the Speech Night. A tradition existing for several years already, this year's Speech Night is now officially named after the current Romanian Minister of Culture Theodor Paleologu, who is also a former ECLA faculty member.

This year there were four areas in which the speakers had to give 3-minute speeches after only 10 minutes of preparation time. The areas were politics, religion, culture, and economics and each area had three or four contestants. Two of the faculty members, David Levine and Daniel Andersson, decided to take part in the fun and compete against their students. The jury consisted of the ISU faculty members who announced the winners at the end of the contest and awarded them with a bottle of wine or champagne.

The topic which invited the biggest number of participants was religion. What the four students probably did not expect when they signed up for this are was the topic: "God is a tyrant." However, all four managed to find their way to tackle it. Andrei Decu (Romania) sent out the thoughtful message: "We don't choose our tyrants, they choose us." On the other hand, Samantha Perera (USA) said it does not really matter whether god is a tyrant or not because "nobody pays attention". The two most contrasting opinions were those of Midori Fujita (Japan) and Mykhaylo Kushnir (Ukraine). Midori distinguished between a dogmatic God and a more personal God, concluding: "of course he is [a tyrant]." Mykhaylo, on the other hand, reminded everyone that God created the world with love and improvised a quotation of the Bible: "As God said, 'Follow me and you will be happy.'" For the discourse on religion, the jury was won over by Samantha's nihilism.

The speech topic for politics was just as controversial: "Toleration is just another word for weakness." Here Ali Ozen (Turkey), Ardi Priks (Estonia), and Mariya Ilieva (Bulgaria) went into abstract discussions of what is weakness but in the end they all seemed to agree with Mariya that "Toleration is strength." The jury also agreed and gave her the first prize.

"Culture is waste" was the unambiguous topic for the discussion on culture. Here Moritz Poesch (Germany) and Nora Georgieva (Bulgaria) had to measure their public speaking abilities against their theater professor David Levine's. Initially, David seemed to defend the position stated in the topic, but he argued that culture constantly tries to overcome its condition. His final challenge to the public was: "But is waste such a bad thing?". Nora seemed to head in the same direction as well, but concluded with the modest statement: "Culture is not waste, it's something a little better." Moritz, however, was a strong defender of the idea that all culture is waste, basing his argument on the readings we had so far. Although the jury found his speech very entertaining in its irony, they chose to award Nora with the coveted bottle of wine.

In the sphere of economics, the contestants took on the ancient fight whether rich people are happier than poor ones. The topic was "The rich do what they can and the poor suffer what they must." Diana Constantinescu (Romania) took a creative approach to the topic and appeared as a slightly arrogant and very nonchalant French banker who was sure of one thing: "Virtue was invented by the poor so that they could cope better with suffering". On the other hand, Jona Dundo (Albania) defended the thesis that being rich is not that good: "We all do what we can and we all suffer what we must." The students in this category competed against the faculty member Daniel Andersson, whose speech took a musical twist as he based his argument on a quote by Ginger Spice from the Spice Girls. "It is the rich who suffer and the poor who are truly rich," he concluded. The winner in this category was Jona.

After the awards were handed out, the night took a completely different shape and students and faculty performed music, playing guitar, violin, and piano and singing. This year's Speech Night ended many hours after it started after performances of songs in many different languages and accompanied by many cheers.

ISU 2009

July 28, 2009

Nora Georgieva (ISU 2009, Bulgaria)

On July 1, students started arriving for this year's ECLA International Summer University (ISU) devoted to "Montaigne and the Making of the Modern Self." The quiet residential neighborhood was awakened by the sound of young people talking excitedly, eager to get to know each other and their new summer home. ISU 2009 began even before the first lecture was held, as the students started discussions on topics ranging from philosophy to the history of their home countries to where in Berlin to go first. This year the 34 students come from 20 countries.

At the end of the first two days, most of the ISU participants ended the day enjoying a drink in the middle of the grass-covered football field between the two residence halls. Several ECLA alumni, Igor Letina (ISU'07, Bosnia and Herzegovina), Snezhina Kovacheva (AY, ISU, Bulgaria) and Daria Coscodan (PY, AY, Moldova) joined the newly arrived and offered advice on the summer university and getting around Berlin. For the ones who stayed out the latest, Daria played several beautiful Portuguese and Moldovan songs.

Part of the first week's activities was devoted to helping the students explore the beautiful city. On the first weekend, students were taken for a walk in the central neighborhood Mitte. The tour was led by art historian Aya Soika, who gave short talks about different historical sites. Ms. Soika led the students through picturesque city Hofs (small squares within the walls of a residential complex), streets with interesting historical stories, and the imposing Museumsinsel (Museum Island). At different times during the first days, students ventured into the various areas of the city on their own, armed with their city guides. Many discovered that getting a little lost in a big city can be quite a challenging and bonding experience.

On July 3, the students officially met the professors at an introductory lecture and a delicious barbeque at which students and faculty broke the ice and informally began their academic dialogue. The introduction was opened by one of ECLA's Co-Deans, Thomas Nørgaard, who encouraged the students to fully enjoy the interdisciplinary approach of ECLA and take the most out of it. Most of the students had not experienced the liberal arts system before. Traditionally for ECLA, the faculty members, just like the students, come from various educational and cultural backgrounds, which makes the exchange of ideas all the more interesting. The ISU 2009 faculty are: Ewa Atanassow (Bulgaria), ECLA faculty; Daniel Andersson (Sweden) who joined ISU this summer; Bartholomew Ryan (Ireland), visiting faculty at ECLA and part of the ISU faculty for the third time, Max Whyte (USA), returning for his second ISU, and the ISU director for the past three years, David Durst (USA).

After the relaxed orientation days, the students focused their attention on their first readings for the following week. This gave the neighborhood the chance to catch its breath and enjoy the silence, but only for a short time. Come back to the ECLA News section in the coming days to find out what happened next.

ECLA GUEST TEACHER: Thomas Doherty on Modernity and the Language of Real Life

July 14, 2009

Elena Volkanovska (2009, Macedonia)

On Wednesday, June 3, Professor Thomas Docherty opened a lecture on Karl Marx's ideology by putting forward a provocative question: Are the days of Marxism really over? Or can we still expect a 'revolution'? Although the question was not weighed down by a serious tone, the presentation and discussion explored the ways in which it remains pertinent.

In order to unfold Marx's ideas and arguments, we turned to Hegel -- or, more precisely, to his followers and his critics. Hegel offered perhaps the most influential philosophy of the working of the state, but both Old and Young Hegelians noted one central failing within it: his theory posits an ideal that the real state, in its everyday functioning, cannot live up to. From this problem derives one of Marx's biggest concerns: what do we do with the discrepancy between the abstract concept of the state, expressed in words, and the experience of those who live within the framework it establishes? Marx describes the criticisms posed by the Young Hegelians as the mere juxtaposition of 'phrases' with 'phrases'. There is a stark difference between things as they really are and the way we represent them (the saying of things). He asks why none of his contemporaries investigate the connection between German philosophy and German reality and thereby connect their criticism to their material context.

Marx seems to claim that the only possible way to bring the state closer to its ideal lies not in reformation, but in dissolution. A new set of material circumstances should be created, and from this world new ideas will arise. Man produces himself through labour, and presents a hinge between the past we have inherited and the future that follows. It is interesting that for Marx, changes in ideas come after the world has changed, and not vice versa, as one might think. God is a product of our consciousness, an alienation of something from within ourselves onto the outside world. Man is an event, an irruption, and has the power to act upon history and to change its course. "Event" is meant in the sense that each action does not have a predictable outcome; something is an event only when we do not know what the outcome was to have been. Marx's view of historical possibility parallels his view of language. Rather than dwelling on its capacity for producing distortion and conflict, he emphasizes, like the Romantic poets, "the real language of men", language as communication between human beings, as real, practical consciousness.

Thomas Docherty is Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Warwick. His main fields of interest are the philosophy of literary criticism, critical theory and the cultural history in relation primarily to European philosophy and literature. Some of his books are Reading (Absent) Character; John Donne Undone; On Modern Authority; Postmodernism; After Theory; Alterities: Criticism and Modernity. His latest book is Aesthetic Democracy.

MONGOLIAN EVENING AT ECLA

July 13, 2009

Elena Volkanovska (2009, Macedonia)

Perhaps one of the most fascinating things about ECLA is its international community. ECLA is a place where one meets people from all over the world, where one can embrace many different cultures by having the world in just one room. On Wednesday, May 27, all the members of the ECLA community had the chance to attend a Mongolian Evening, dedicated to the presentation of Mongolian traditions and culture.

Tuvshinzaya Gantulga (AY 2009, Mongolia) opened the evening with a very sincere confession: "If I-a Mongolian-would never talk about my country, never make my culture accessible, how could I expect others to know about my country?" For his speech, Tuvshinzaya prepared answers to the questions most frequently asked by students. This proved to be the right method, mostly because the questions were so honest, a true blend of natural curiosity and a will to learn more. In order to present a clearer picture, he constantly made comparisons which were familiar to everyone, so that we were acquainted not only with the meaning of what he introduced in numbers or words, but we also managed to truly grasp what he was referring to by having it presented in concepts close to our established way of understanding. For example, Mongolia is "four times larger than Germany".

This brief explanation of Mongolia's tradition, culture and history was followed by the introduction of the Mongolian ambassador to Germany, Dr. Galbaatar Tuvdendorj, who addressed the audience and talked in more detail about the turbulent changes in the political organization of the country that took place over the past years, the impact these changes had on society, and the current situation in Mongolia. As far as economy is concerned, Mongolia, like the rest of the countries in the world, is caught up in the financial crisis that has been shaking the world over the past year. What is important is that Mongolia is focused on education and makes sure that its students have the opportunity to study abroad so that later on they can apply their knowledge to better the prospects of their country. Dr. Galbaatar, who, prior to accepting his post as an ambassador in Germany, was the Vice President of the Mongolian Academy of Science, said that he was very pleasantly surprised by ECLA's programme and the focus it has on an understanding of values. He believes that it is exactly this focus that the world lacks, and that only through respecting values can we strive towards the establishment of peace and balance in this world.

After Dr. Galbaatar's speech, we enjoyed some traditional Mongolian dishes -- such as "Buuz" or "Бууз", traditionally eaten at home at the Mongolian New Year. What followed was a live performance by the Mongolian folk band Egshiglen in our lecture hall. At once, past and present were intermingled as the building was filled with the sounds of traditional Mongolian music, which both calmed and excited the spirit. This created a perfect atmosphere, suitable to wrap up this evening into one of the best presents that we could ever get. So, Bayarlalaa (Mongolian for thank you!) to the guests and to everyone who participated in the organization, who made this possible and who took care that we could experience such a palpably authentic event.

Traditions Must Be Kept

June 10, 2009

Brindusa Birhala (PY09, Romania)

Should anybody ask us how the 1st of May in Berlin was, we could not provide any testimony to it, because ECLA journeyed to Weimar for the whole weekend. One more proof that we here are not street fighters, but passionate lovers...of culture! The bright and early start at 7 a.m. might have seemed extreme to a few, but once cosily arranged in the bus, sleep took over the crew faster than you can say "Autobahn". Unfortunately the regular 'mastermind' of the ECLA annual Weimar trip, German language instructor Dirk Deichfuss could not join us, but his presence was felt in the tip-top organization and in the choice of an 'echte Deutsche Jugendherberge', where we spent the night. To replace him, residential life coordinator Zoltan Helmich filled the necessary role of jack-of-all-trades, which included everything from tour guide to bus paparazzo.

Opening our eyes to Weimar requested several leaps into the past, to the times of Goethe and Schiller, also earlier, to those of Lucas Cranach, and to the more recent Bauhaus School. Very appreciative of its rich cultural heritage, this town knows how to display it to any bunch of curious tourists like us. Posters announced the celebration of 90 years of Bauhaus, several congresses, and the staging of Romeo and Juliet at the German National Theatre. The sound of hoofs on cobblestone announcing carriages, people in XVIII Century costumes, and meandering narrow streets make this little town appear intrusively surreal. Thank God for the popular celebration in the main square to remind us that there are still wursts and politics in Germany. Especially on the 1st of May!

Some of us could not resist the welcoming cafés; others rushed to the huge Park on the Ilm, while the rest hid away from the sunny day within the walls of museums. I admit being in the last category, but it also includes the German art class who spent their free time in the Bauhaus Museum. Schiller's house, The Weimar Town museum, Anna Amalia Library, and the Nietzsche Archive were among the places that lured some of us for short visits. We later reunited to fulfil an important tradition for ECLA: the visit to the Goethe National Museum. This is the house which the poet received from Carl August, grand duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach in 1792, and in which he lived after his return from Italy, for almost 50 years, until his death. The building was opened as a memorial building half a century later.

One can't expect to grasp his genius solely in the many exquisite objects that he collected or received over the years, but the visit is certainly awe-inspiring each time. The museum guide presented the cult-corners of the house such as his library, his study-room and the simple room in which he died, which are accessible to the visitors only from afar. To complement this tour, we headed to Goethe's first abode in Weimar, his Garden House in the park, and paid tribute to another tradition-playing Frisbee together in the lush surroundings. Just as important, I should not forget to mention the wonderful dinner together and the nocturnal walk to the hostel.

Saturday was 'wander-full', as the bus took us outside Weimar and placed us on Goethe's trekking route - the 28-kilometre "Wanderweg" from Weimar to Großkochberg. It's not difficult to imagine the natural landscape along the way inspiring Goethe to produce one of the most famous lyric poems in German literature, the Wanderer's Nightsong. En route we ran into dedicated Goethe "pilgrims" who keep the tradition by walking the entire length through the same meadows and villages that carried the steps of the naturalist through Thuringia. Goethe needed only 4 hours for this trip, but we lingered from one pleasant conversation to another and took plenty of time to admire the scenery, especially at the end of the route, where we climbed up Luisen tower and exchanged smiles with the crowd of summery German wanderers. This part of the Weimar excursion was included for the first time this year; it was such a perfect ending and celebration of Goethe's spirit, effectively fusing us into a community, that it surely made itself eligible to become another ECLA tradition.

Family Portrait

June 9, 2009

Brindusa Birhala (PY09, Romania)

We use our beautiful campus gardens in a variety of ways: student-professor football, volleyball, or badminton matches, mastering the Frisbee, sunbathing, reading or sleeping in the grass, and even treasure hunting. Elizabeth Hanka (AY, USA) proposed dining there too, and the idea expanded to that of a barbecue in the garden, which warmly welcomed everyone from the present student-body, faculty and administration. One of the skillful people behind the grill was Adrian Nicolae, alumnus of the AY 2005-06 program, currently an MA student in Bonn, who coincidentally was an overnight guest. Without doubt he easily connected with the current class and attracted our interest, mostly since he was the one grilling our potatoes. He admitted to being struck by nostalgia, and to being happy to be back in these gardens.

Elizabeth's idea coincided with her bicycle community project, and afforded an opportunity to finish a process that had been in the works since the first weeks of the school year. Her proposal that students should be supported in buying bicycles to use during the year resulted in people pairing up to buy bicycles at the Mauerpark flea market, for which they were then reimbursed. Everyone had bought their bicycles by the end of the winter term, and it was a relief to have such an easy way to get off campus and explore the city when the spring came. However, the project was not complete, as another part of it, aside from simply having the bikes to share and use, was to make them community bikes by decorating them. After much debate about whether to paint them all, attach some kind of sign to them, or put stickers on them, we finally decided on the sticker method. Each student was presented with a veritable rainbow of stickers, and getting together for the barbecue proved to be a great opportunity to "rebrand" the bicycles we have been using since spring. Brightly coloured ECLA stickers signal now that there's something special about our bikes, something that is worth checking out. Because they are being pedaled throughout the city by students eager to discover it, we expect the stickers to become visit cards in motion.

We were pleased to be able to host faculty members and their families at our barbecue, and be able to converse with them on the grassy background instead of in the usual classroom buildings. I personally enjoyed the company of "little ECLA", the young children of our faculty and staff; they got to know each other, and carried important debates around the ownership of toys. The contributions of various students' personal recipes, experimentations and collaborations, combined with dishes generously brought by faculty members, made for a diverse and delicious feast. The party was also encouraged by the expertise of some of our more technically minded students who spontaneously hooked up a sound system to which we took turns attaching our laptops to for a variety of music. After a full and satisfying day, things wound down into the night as small groups stayed on the lawn reflecting on the experience of being here together before drifting off to bed.

Whose Is That Wall?

June 04, 2009

Brindusa Birhala (PY09, Romania)

The very first event of State of the World Week materialized with the support of ECLA art history faculty Aya Soika and addressed one of the many features of Berlin that I find particularly fascinating -the ubiquitous street art. I became a discoverer of street art when I saw that familiar cities 'back home' were no longer neutral, but had started to engage each pedestrian with their playfulness. Suddenly, forgotten corners of Bucharest, Brasov or Timisoara blossomed into gems of style and wit through which one 'reads' how a special group of dwellers lovingly approach their cities and poke at the indifference of others. No surprise that once I got the chance to live in Berlin, I felt like a child in a candy store. Walking (or biking) though the streets here comes close to reading a perpetually changing comic book. For this reason, I needed to transmit a dose of my exhilaration to those ECLA classmates with an eye prepared to see art in the most unexpected sites. My proposal for this years' SWWE was a presentation of street art and the question of ownership, followed by a walk through Kreuzberg where we got more acquainted with the 'works' and, indirectly, with the artists.

What we call 'street art' now is an umbrella term which originated in 1960s wall scribbling, and which expanded to include other manifestations that share a fundamental characteristic: using public space as display. Spray-painted names or words on building façades were a nuisance to everybody, initially; regarded as vandalism and punished by state authorities, this set the course for many of the practices still present in street art operations: the anonymity of the artists, the speed at which they work (prompted by the fear of being arrested), the formation of a 'behind-the-scenes' community, and the ephemeral and critical nature of this art. The scope is now international, no longer restricted to an urban setting, and by gaining the appreciation of city dwellers, it gradually grows out of its illegal relation with the city authorities. Nonetheless, this is a slow process undercut by massive arrests and rapid defacing of the works, even in cities where street art is old news by now.

The controversy behind this practice offers various opportunities to ask the question: Who does a wall belong to? One could argue that since the artists remain anonymous and use public space as display, street art should be viewed as an act 'of the people for the people'. Its critical discourse seems to point in the same direction, with works that either illustrate the problems of the neighbourhood community or carry a broader counter-cultural message. The first level of inquiry in my presentation was the legitimacy of using public space as display and an examination of the many functions of street art: as protest, to entertain, to represent, or to embellish the streets. I embrace the interpretation of street art as standing in opposition with consumer society; through its discourse, it exposes the pervasiveness of outdoor advertising that clogs up public space and laments the complacent attitudes of both citizens and authorities towards it.

The growing popularity of the genre sends the works into art galleries (albeit of the 'alternative' variety) and generates international recognition for the artists. As a result of the latter, we now see strange paradoxes such as the auctioning of pieces of street art, or neighbourhood inhabitants raging about 'their' street art being vandalized (covered up or tainted by anti-graffiti groups). Insofar as artists (or groups) develop their recognizable styles and tags, street-art pieces are associated with them, and are thought to belong to them. At the same time, people who encounter them every day develop feelings of attachment and regard their disappearance as a theft from their common property. The artists one tends to associate with Berlin are already consecrated 'travelling acts' like BLU, Banksy, JR and Os Gemenos, whose works are large scale and have been legally produced under the tutelage of street art festivals financed from the city's culture funds. Nonetheless, for me, street art maintains its flavour when it sneaks onto the wall illegally and unexpectedly overnight, like in the repetitive characters of 'local' artists Nomad, CupK, Alias, XOOOOX, or MYMO. Thinking about ownership in relation to street art makes one wonder whether the concept of ownership per se is not outside the scope of this genre.

SWWE GUEST LECTURER: Volker Wiese: Seminar on "Legal Issues in the Restitution of Cultural Heritage"

May 24, 2009

Snezhina Kovacheva (2009, Bulgaria)

Monday's theme on restitution was further developed in an afternoon seminar led by Dr. Volker Wiese from Bucerius Law School. The main goal of the seminar was to examine several legal aspects of the restitution of cultural heritage. The discussion centred on the essence, as well as the legal and ethical implications, of the concept lex rei sita, which stipulates that "questions related to the validity of a transfer of personal property are governed by the law of the state where the property is located at the time of the alleged transfer."

Students, faculty and Dr. Wiese explored how the trade and restitution of culturally significant objects is complicated by the diversity of local laws that concern bona fide purchasers - buyers who acquire a cultural item in accordance with local trade laws and are not aware of the special provenance of the item, which belongs to the cultural heritage of a foreign country. While in Germany, bona fide purchasers become lawful owners as long as the object has not been stolen before, Anglo-American laws do not apply the concept of bona fide acquisition of property at all. On the other end of the legal spectrum, under Italian law bona fide purchasers are honoured even when it becomes known that the property had been stolen before from its original owner. The seminar participants discussed how specific historical and cultural developments in each country might have contributed to the formation of a particular legal view on bona fide purchases. To illustrate the practical significance of the fact that the international community does not have a standardized international framework, Dr. Wise presented several insightful cases where local laws are recognized in the case of a sale even if the cultural item has been abducted from a legal order that does not follow the concept of bona fide purchase, and has been subsequently brought back to that country.

The seminar also considered the issue of declaring cultural objects res extra commercium, which makes the objects themselves non-tradable, and the transfer of their ownership legally void. However, the international treatment of such cases is not uniform, Dr. Wiese pointed out. He first presented a case in Italy, where the courts established that the rule shall be strictly confined to the territory of the original state. In effect, this makes it legally permissible for a cultural object declared res extra commercium in Spain, for example, to be traded in the territory of Italy. Dr. Wiese juxtaposed this case with the ruling of a French court, which argued that the legal nature of a foreign res extra commercium cannot be domestically disregarded.

The seminar scrutinized the soundness of legal rules when applied to the special intellectual context of cultural items, and considered whether and to what extent legal rules can and should reflect intricate ethical judgment and embody changing moral codes. A wide variety of relevant questions were discussed, including whether the law should foster trade with cultural items or embody policies that tie the objects more strongly to their country of origin, and what the implications are for cultural exchange and the preservation of cultural heritage.

Volker Wiese teaches at Bucerius Law School in Hamburg and specializes in restitution policies. He obtained a Master of Laws (LL.M.) from McGill University for his thesis: "A new Approach to the Private International Law of Copyright" and a PhD. from Bucerius Law School in 2005, on "The Influence of European Law on International Property Law pertaining to Cultural Property".

SWWE GUEST LECTURER Daniel Butt: Cultural Property and Cultural Heritage - who owns what, and why? What should museums and collectors give back, and what should they keep?

May 24, 2009

Snezhina Kovacheva (2009, Bulgaria)

May 11 - the first day of ECLA's State of the World Week (SWWE), a forum for inquiry into current affairs - was devoted to the concept of restitution. In the morning, Daniel Butt from Oxford gave a lecture on the theoretical foundation of contemporary claims for compensation and property restitution, which arise as a result of past wrongdoing between nations. Butt framed this discussion within the larger theoretical context of property ownership.

Butt distinguished between two fundamentally different views on distributive justice: forward-looking, primarily concerned with generational redistribution, and backward-looking, which focuses on the historic entitlement to property. Butt explained that proponents of the former principle usually criticize the latter from two distinct perspectives: equality of opportunity and efficiency. Egalitarians disapprove of how the property mechanism helps perpetuate and accentuate a division among people that is arbitrary from a moral point of view. At the same time, consequentialists find it problematic that property rights obstruct the optimal use of resources from a societal perspective (i.e. a particular piece of land may have yielded higher output if maintained by a professional agriculturalist, rather than by its owner).

Butt's goal was not to present in further detail divergent perspectives in the intellectual discourse on property (which ECLA students are approaching as a part of their AY core course on the same topic). After briefly referencing contributions of such major thinkers as John Rawls and Robert Nozick, the lecturer primarily focused on the domain of cultural property, beginning by pointing out an inconsistency among some vocal advocates of a cosmopolitan view on cultural property. According to this group, cultural heritage belongs to humanity as a whole and preservation overrides historic concerns. But while some "redistributive cosmopolitans" object to the possibility and necessity of rectification of historic international injustice in the context of cultural property, they do not support the large scale general redistribution that would seem to be consistent with their own principle and argumentation. Butt emphasized that such a dualistic attitude is inconsistent and thus problematic in a world where "ownership matters."

For a backward-looking theory of distributive justice to work, one needs to ascertain the legitimacy of initial property holding and the justifiability of inheritance, Butt established. He commented on each concept and put forward arguments as to why the acquisition of cultural property might be less problematic than that of land, natural resources and money. He then proceeded by enumerating the major elements behind the theory of correcting historic international injustice through restitution: 1) there has been a victim of injustice and a respective benefactor; 2) collectives exist that have failed to correct past wrongs, and 3) the descendants of the victims have at least moral, if not legal, entitlement to the particular object(s).

Butt explained how attributing property to national collectives is the best response to indeterminacy and diffusion of ownership in the cases when much time has passed since the act of injustice. He also elaborated that the failure to rectify injustice may give rise to due compensation for the period during which a nation has been benefiting from the possession of the cultural property in question. In response to the "noble preservationists," who claim that -but for their intervention - the property might otherwise have been destroyed or not taken care of, Butt replied that preservation may deserve praise and compensation, but does not obliterate prior entitlements to the object or confer absolute property rights to the current keeper.

The lecture called attention to the idea that a policy of cultural-property restitution would not lead to an ominous worldwide reshuffling of museum holdings wreaking havoc among most museums, since much cultural property was produced for trade and acquired fairly. Butt also outlined a practical mechanism for classifying cultural property into four categories: 1) culturally central; 2) culturally peripheral; 3) intrinsically sensitive (when a community does not wish objects to be displayed in public, e.g., human remains), and 4) circumstantially sensitive (when a national collective is especially concerned with the fact that a particular nation, such as a former conqueror or colonial power, possesses an object deemed culturally important).

In his afternoon seminar, Butt used a case-based approach to illustrate the intricacies and ambiguities of real-world restitution. Students and faculty discussed the moral justifications for returning to Greece the Elgin Marbles, a collection of classical marble sculptures, originally a part of the Parthenon in Athens and currently in the British Museum in London. The grounds for restitution were also discussed in the cases of Benin marble sculptures appropriated by the British Empire in 1897; the partial return the Teotihuacan murals to Mexico by USA; the looting of art in Nazi Germany, and the public display of shrunken heads that belong to an ancient tribe, at the Pitt River Museum in Oxford.

Daniel Butt teaches at the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Oxford. His primary research focus is on questions of global justice, in particular on normative questions relating to the rectification of historic international injustice. His book Rectifying International Injustice: Principles of Compensation and Restitution Between Nations, excerpts from which were read by ECLA students as preparation for his lecture and seminar, has just been published by Oxford University Press (2009).

STATE OF THE WORLD WEEK AT ECLA 2009

May 13, 2009

Press Release

Monday, May 11, was the first day of this year's State of the World Week at ECLA (SWWE) dedicated to the theme "The Politics of Cultural Ownership." The week-long series of events (May 11 - 15) constitute a forum for inquiry into current affairs, and is planned by faculty and students together. SWWE fulfils an integral part of ECLA's educational mission by demonstrating the relevance of Liberal Arts studies to contemporary world events.

The issues and questions examined this week include: Who owns artefacts in museums? Who has the right to decide whether an art work should be restored? Who has the authority to speak for a culture threatened by collapse? Can cultural identity itself be an object of ownership? What happens to the notions of copyright and intellectual property in the era of the internet, new media and file-sharing? SWWE presents a platform for leading scholars, artists and other experts - together with faculty and students - to explore what happens when the ownership of art is challenged. The topic raises questions that are strongly linked to the Academy Year core course on the concept of 'Property' in modernity.

Speakers at SWWE include:

DANIEL BUTT, Fellow and Tutor in Politics, Oriel College, Oxford. Writer of Rectifying International Injustice

VOLKER WIESE, teaches at the Bucerius Law School in Hamburg and specialises in restiution policies.

JOY GARNETT, College Art Association's Committee for Intellectual Property, Arts Editor for the scholarly journal Cultural Politics

RUTH FRANKLIN , Senior Editor at The New Republic.

DENISE BUDD, Lecturer-in-Discipline in the Core Curriculum at Columbia University, and the Director of ArtWatch International

RICHARD FREMANTLE, writer, art historian, lecturer, and collector of contemporary art, who will join ECLA's sessions on Art Restoration

SWWE's opening dinner on Sunday, May 10, was held at "Feast," a transformed shop space in Berlin's Neukölln district that brought together guests, faculty and students. The presence of owner Suzy Fracassa, the excellent service of her catering company and the simple yet charming interior decoration contributed to the unique atmosphere of the event.

For more information, a detailed description of the events and biographies of the guest-lecturers, visit the official State of the World Week at ECLA website (swwe.ecla.de).

A SUNDAY AFTERNOON AT THE BERGGRUEN MUSEUM

May 12, 2009

Snezhina Kovacheva (2009, Bulgaria)

ECLA students enrolled in the elective class "Methods and Interpretations: The Visual Arts" spent an exciting afternoon at the Museum Berggruen in Berlin's Charlottenburg district. The students confidently took up the challenge of applying visual analysis to major works of European modernism, and the museum provided a perfect setting with its works by Picasso, Matisse, Klee and Giacometti.

The vibrant discussion commenced with a brief overview of how twentieth-century art is different from the Renaissance tradition, and how the canvas is no longer essentially an Albertian window, which, through perspective, allows us to look into another world. The class interpreted "Le Cahier Bleu" (1945) and "Intérieur en Entretat" (1920) by Matisse in the light of how the tenets of realism and naturalism have given way to a new understanding and sensation, which acknowledges the reality of the two-dimensional flat surface, as well as that of the brushstroke. By scrutinizing representative works by Matisse from earlier and later in his career, the students could trace the rising importance of surface and color, and soon found themselves beyond the realm of formal analysis, elaborating on the subjective emotions that a painting provokes in the audience, and on the importance of pure form and of medium as a part of "the message."

Berggruen's impressive collection of Picasso paintings constituted an excellent opportunity for discovering how the artist kept transforming and reinventing himself throughout his various periods. The students spent most of the time engaging with cubist works, distilling the essence of the style and experiencing the active role that viewers should adopt in order to decipher the suggested meanings behind increasingly abstract representations. Insightful juxtaposition between Braque and Picasso made it possible to further refine one's comprehension of both the aesthetic principles behind cubism and the subtle characteristics that make the work of each representative of the movement unique and recognizable.

A preparatory sketch by Picasso for the famous "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon"(1907), presented together with African artifacts, triggered a discussion about the significance of primitive art for modernists, with a special emphasis on the ambiguity of how artists interpreted exotic objects: on the one hand, as a source of inspiration full of vitality and spirituality, and on the other, as items devoid of context onto which pre-conceived Western notions were sometimes applied too hastily.

Another painting by Picasso - "La Minotauromachie" (1936) - served as a brilliant example of the artist's mythic sensibility and self-produced iconography, in which references to other Picasso works are often more enlightening than an examination of the generally accepted symbolism of particular images in the context of art history. For example, while in other contexts the Minotaur - the part-bull part-man creature from Greek mythology - may stand for the general bestial nature of humans, for Picasso it is often associated with virulent masculine sexuality.

The Berggruen Museum is named after Heinz Berggruen - a prominent German art dealer and collector who left his art-collection to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, and made it public in 1996. Berggruen, whose passion was modern art from the beginning of the 20th century, died in 2007, having led a remarkable life. Born in 1914, he immigrated to the United States in 1936 to escape from Nazi Germany; held the office of "assistant director" at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; had a short passionate affair with painter Frida Kahlo; became Picasso's art-dealer after the Second World War, and was awarded honorary citizenship of Berlin, as well as the Federal Cross of Merit of Germany. ECLA students in the past (i.e., ISU 2004) have had the honor and pleasure to personally meet Mr. Berggruen during a museum tour, and to listen to his fascinating stories about several of the displayed works.

ITALY TRIP

May 12, 2009

Elena Volkanovska (2009, Macedonia)

Elizabeth Hanka (2009, USA)

In the dawn light of Sunday, March 15, the 35 AY students embarked on a mission to trace the beginning of the Renaissance by exploring its heart -- Florence. By the time the plane landed in Rome, everyone was full of excitement about what was yet to come. On our way from Rome to Florence, we made short stops in two small towns -- Pienza and Arezzo. Our "strategy" there was to gather at the town square and then disperse and disappear into the small alleys on a quest for the coziest café we could find to provide us with an unforgettable experience of Italy's famous coffee. We also paid a visit to the Sanctuary of San Biagio in Montepulciano, a 16th century Tuscan building just outside the city.

The night had sneaked into Florence before us: by the time we arrived at our final stop, the city's pulse was already slow and calm. Happily tired, we got to our hotel, which was on a very convenient site, its main entrance facing the Basilica di San Lorenzo. The wide street in front of our hotel turned into a noisy marketplace in the mornings. The hotel itself was nice and welcoming, with rooms furnished in a vintage style.

The study trip was officially opened with a visit to the Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore, also known as "el Duomo" - the main cathedral of the city of Florence. Its foundation stone was laid in 1296, but it was not until 1436 that this majestic edifice was completed. It was actually built upon the ruins of an earlier, smaller cathedral, which was dedicated to Santa Reparata. This new cathedral is famous for many things, one of them being the majestic cupola constructed by Brunelleschi. He faced the challenge of doing something that had never been done before -- he had an idea of constructing out of brick a massive cupola in the fashion of the great dome of the Pantheon in Rome. The difference in material proved to be more difficult than expected. This challenge, however, was very advantageous for Brunelleschi, since it revealed his genius in full light and secured his name among the most renowned architects of all times. He put his theories into practice by engineering a double-walled, octagonal dome, for the construction of which he also invented hoisting machines. The interior of the dome is decorated with frescoes by Giorgio Vasari and Federico Zuccari. The cathedral houses works by Michelino, Paolo Uccello and Andrea del Castagno. A magnificent view of Florence is the reward for climbing to the top of the dome. Outside the cathedral is the Baptistery of St. John, famous for its set of bronze doors designed by Lorenzo Ghiberti. The craftsmanship with which these doors were made, as well as their extreme beauty, earned them a very flattering name -- they were called "the doors of paradise" by Michelangelo.

This visit was the best way to start the week -- it was a successful, as well as a motivating, introduction for the things that were to follow it. Some of the most interesting were the Palazzo Vecchio, the town hall of Florence which overlooks the Piazza della Signoria; the Bargello Palace, an art museum which was a prison during the 16th century; the Ufizzi Gallery, the Laurentian Library and the Academia, which houses one of the Renaissance's finest pearls: the legendary David by Michelangelo.

After some tours and explorations of the city, our first day in Florence culminated in a kind of pilgrimage across the river Arno, through winding back streets, past the city gates and up a long stairway to San Miniato al Monte, a medieval church overlooking the city. The steps up the hill, marked by posts invoking the seven stations of the cross, is supposed to be reminiscent of Christ's long journey up to Golgotha. While the difficulty of the climb is certainly exaggerated, after having been to the top of the Duomo in the morning, it made for a long day of upward movement. Once we got to the top and entered the church grounds by a side entrance, it was certainly worth it.

We were able to take a step back to see this famous city from above and outside, getting a feel for the poetry of the whole, seeing the Duomo and all the other legendary buildings in their context.

Built in the 11th century, San Miniato seemed outside the Renaissance city of Florence in more ways than one. Upon entering the church the sense of departure was strengthened even further by the cool darkness and the chanting heard emanating from deep within the church. We made our way to the back of the church, behind a screen, where we caught a glimpse of an evening mass in the crypt which lies beneath the unusual raised choir containing a Romanesque pulpit dating from 1207.

The crypt is supposed by some to contain the bones of St. Miniato, who, because he was a Christian, was thrown to a panther, who refused to eat him. He was then beheaded, but he picked up his head and carried it across the Arno and up to this hill where he died.

After looking at the 14th century frescoes and around the rest of the church, we made our way to the shaft of evening light indicating the door, and stepped out into the setting sun. We picnicked on the wall looking out over the city before heading back down into the hubbub of the city, tired but satisfied.

Hosted by Veronica Vaca Moreno (Ecuador) and Isolina Lopez Rivarola (Argentina)and the Florentine restaurant staff, we all crowded into Trattoria Anita on Thursday night for the ECLA dinner. After being divided into our various tour groups throughout the week, it was nice to come together and have a chance to see everyone's face in one room and share our experiences of the week's adventures. Instructed by elegant notecards on where to sit, and told by a hand written menu what we would be eating, we had only to sit together and talk about how it felt to be in Florence while they brought out red wine, roast pork appetizers and pasta with traditional red sauce. Faculty were mixed with students so that interesting discussions of how this year's trip compared to other years, and what things we shouldn't miss before leaving immediately emerged. Lynn Catterson (Guest Professor, Columbia University) shared insider tips on where to eat and her aspirations for this study trip as an ECLA tradition. .

Friday morning found us commencing the long awaited encounter with Michelangelo. We began the meeting in the Medici Chapel of the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo. The New Sacristy houses the tombs of Guiliano and Lorenzo di Medici, graced by Michelangelo's sculptures of Day, Night, and the Active Life, and Dawn, Dusk, and the Contemplative Life, respectively. Lynn Catterson demonstrated to us the incredible sense of motion in the room achieved not only by the postures of the statues, but also by their gazes. In following these gazes, one's eye immediately travels around in an ever upward spiraling movement, indicative of Michelangelo's Neoplatonic sensibilities.

After lunch we continued with Geoff Lehman's introduction to the Laurentian library, whose architecture distinctly and profoundly speaks of Michelangelo in its mannerism, and continuation of the Neoplatonic theme of upward movement coupled with bodily torment. The sense one has standing in this room is one of claustrophobia in the face of an immense architecture that one might expect to find on the exterior of a building.

Our Neoplatonic dialogue culminated with a visit to l'Accademia, where Michelangelo's slaves greeted us upon entering. Originally part of the design for the unfinished tomb of Pope Julius II, the slaves flanked the wide corridor, both arresting the eye, and leading it onward to the David, which awed each person as they entered to see this immense work of genius.

Seeing the David, even after such a day, was an experience unlike any other. Upon entering the room, suddenly one felt an understanding of exactly how Michelangelo must have made the statue at the very same moment that one is struck by the seeming impossibility that such a creation could come from one human being. The statue is not only a depiction of a great hero about to act, but also an embodiment of a boy about to become a man, a block of marble caught between the real and the imagined. In this term dedicated to the discovery of the beauty and divinity of humanity and the human soul through the human body and the artistry of genius, to end the trip with a close encounter with this statue, so fluid and yet so fixed in between marble and human flesh, between human and divine, between boy and man, seemed to be a perfect closing and a perfect opening to all the questions that ever remain just beyond our grasp.

ECLA IN MILAN

May 11, 2009

Snezhina Kovacheva (2009, Bulgaria)

ECLA's day-trip to Milan, part of the weeklong study trip to Italy, was an exciting adventure in the heart of the second largest city and largest metropolitan area in Italy, also known as the world capital of design and fashion. With the virtuoso guidance of ECLA Laura Scuriatti - a native Milanese - the city's historical and architectural charm, as well as artistic treasures began to unfold in front of the eyes of ECLA students and faculty.

Our immersion in Milanese cultural heritage began at Piazza Duomo with a visit to the Milan Cathedral (Duomo di Milano), the biggest and greatest example of Gothic architecture in Italy and third largest in the world, after St. Peter's Basilica in Rome and the Cathedral of Seville. Begun in 1386 with its façade started in 1567 and the front-works finished in 1805, the Duomo boasts a history that spans more than 4 centuries. Such a breathtaking setting provided not only for a discussion about the development of different architectural styles, but also for insightful reflection on the cathedral's significance for Milan's general history.

ECLA's tour continued in Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, the oldest museum in Milan located at the premises of Biblioteca Ambrosiana, a historic library containing nearly 12,000 drawings by European artists from the 14th to the 19th century. The highlights included Leonardo da Vinci's Atlantic Codex (Codex Atlanticus), a remarkable, twelve-volume, bound set of drawings and writings on subjects ranging from flight to weaponry and from musical instruments to mathematics and botany. The precious displays triggered an exuberant conversation about Leonardo's diaries and drawings, which we had read closely as a part of the "Arts and Politics in Renaissance Florence" curriculum. Rafael's gigantic preliminary drawing for the fresco "School of Athens," itself located in the Vatican in Rome, was an equally captivating opportunity to scrutinize the painter's technique and style.