News 2011

THE MAGUS OF THE NORTH: JOHANN GEORG HAMANN

August 10, 2011

Eugen Rosso (4th year BA, Romania)

Johann Georg Hamann is arguably the most extraordinary thinker and writer of the late 18th century, and studying his works leads one to wonder why he is so little known.

Compared with his contemporaries such as Immanuel Kant who was his friend, (although they were usually in radical disagreement on philosophical matters) and those who were influenced by him in various ways-he was the mentor of Herder, drew Hegel's admiration and Goethe's enthusiastic praise, and was a major influence on Kierkegaard, as important as Hamann is as a thinker and writer, few people nowadays have heard of him, which is a terrible loss.

One of the most important reasons for his relative obscurity must be the fact that Hamann's approach differed sharply from the common ways of thinking and writing of his time, which are in many respects very similar to ours. Throughout the whole of intellectual history there are very few thinkers who, compared with the time they lived in, can be truly called non-conformist.

Hamann, who was known by the nickname 'Magus im Norden' - 'the Magus of the North', had a very skeptical attitude towards the Enlightenment, and thus willfully adopted a writing style radically opposed to the prevailing one, influenced by Enlightenment ideals.

From our ISU Prussia readings so far, we are familiar with this latter style from reading the essays by Mendelssohn, Kant and Fichte, and also from our modern 'academic style' of writing, which aims towards similar standards: clear, orderly, objective, impersonal, with few, if any, references to tradition, the historical circumstances of the author, or the author's personal history-and, perhaps most importantly, serious in tone, with little, if any, humor.

In contrast, Hamann's own style goes completely against this ideal: he avoids systematic, ordered exposition and instead writes short essays, not treatises or books. He uses parody and satire extensively; he employs an enormous wealth and breadth of classical, Biblical, historical and personal references and allusions - mostly to humorous effect, and does not seem at all concerned with making himself clear and easy to understand.

Hamann's style was notoriously challenging even in his own age, and will certainly baffle a first-time modern reader. His works might seem like they consists of a series of obscure and oracular riddles, unless one has the benefit of a critical translation, footnotes and explanations of the relevant references, which is enormously helpful and makes studying him quite pleasant. Fortunately, there are very good English translations of this kind that have been published in recent years.

But dismissing Hamann as a thinker because he does not conform to our comfortable expectations of what philosophy should 'look like' would be a terrible mistake, if we are at all interested in going beyond what we are taught to be comfortable with. Likewise, his pervasive humor (Kierkegaard calls him 'the greatest and most authentic humorist' of all time) is not what we are taught to associate with 'serious', intelligent thought and analysis.

Yet, all these standards of 'serious writing' were already there in Hamann's time, and his refusal to conform to, or even compromise with them for the sake of public recognition, should itself draw our attention to him more than to any other thinker from the Enlightenment age - if we truly value independence and courage in matters of thought as much as we claim.

And there is indeed very much to gain, on all levels, from studying Hamann and taking him seriously (even, or especially, when he is joking). For example, we can look at his response and critique of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, titled 'Metacritique of the Purism of Reason', in which Hamann presents a very powerful counter-argument to the Kantian project, which he applies to the Enlightenment as a whole.

He argues, on linguistic grounds, that the Enlightenment drive towards 'purifying' reason of everything which is traditional and historical is bound to fail. This is because all Enlightenment theories about reason, Kant's system included (and any attempt towards systematic thought), inevitably employ language, which is itself a historical and traditional object that develops and changes its rules over time in decidedly non-rational ways.

Thus, the adherents of the Enlightenment cannot possibly justify their claims to universal certainty, independent of all history and tradition. Language must be used, reason is never 'pure', nor can it ever be, and thus it cannot claim to judge all reality 'from outside', or to be able to make a radical break with its own past. This is a weighty argument, then and now, against not only rationalism, but ultimately against ideology in all its forms.

Still, valuable as his critiques of his contemporaries undoubtedly are, I feel that Hamann's greatness as a thinker can only be gleaned from examining his original contributions to intellectual history. Let us look closely at one of his famous witticisms: "I look upon logical proofs the way a well-bred girl looks upon a love letter". On the surface, this is only a humorous analogy expressing his own position towards the rationalistic arguments common during the Enlightenment. But if we dig deeper into the meaning of this statement, we find that it conceals, so to speak, much buried treasure.

We have here a subtle reference to Plato's dialogue Phaedrus, which is centered around love speeches, and we need to examine the dialogue closely to find out how the activity of the philosopher, which for Socrates fundamentally involves the mysterious 'erotic art' (the only one in which he claims any skill), is inextricably connected with precisely such love speeches.

Then, we also need to examine Plato's Symposium, where Socrates gives an account of these matters which is interestingly different, but which seems to affirm the same fundamental thesis that not only is love philosophical, and thus love-letters are too, but philosophical writings are always love letters of a particular sort - we might venture to say love letters for the soul.

This is very relevant for Hamann's project as the word for 'soul', psyche, is always feminine in Greek. And what better attitude might a student of such 'love letters' have in such matters than employing the self-control, modesty, awareness of the great value of what is at stake, and a healthy skepticism - all traits peculiar to a 'well-bred girl'?

Of course, I have only provided here a vague outline of the kind of argument that Hamann's witticism suggests. Indeed, it would take a book-length study of the Platonic dialogues involved to establish my thesis conclusively. But it is Hamann's thinking and writing which opens the door to such an unusual and promising line of thought, and it is this inestimably precious quality I have found in very few other thinkers indeed.

MUSIC: CONNECTING PEOPLE

August 10, 2011

Gjurgica Ilieva (ISU'11, Macedonia)

The first few weeks of the ISU pushed us into a whirlwind of new impressions consisting of lots of historical and cultural visits all around Berlin, lectures and seminars on Prussia's history. In between, there are the small night escapades that all of us made individually.

Somewhere in the middle of ISU week two, I decided to stop for a minute and look back at these past two weeks. Something was missing, I realised, and after some thinking, it became clear that somehow we missed the social part of this summer school. How are we to rectify that I thought? How do we get to do some bonding?

The answer to this riddle came out of the blue, in the form of the short and completely spontaneous guitar show that we attended last Wednesday. Peter's birthday being the excuse for the gathering, we stayed on the lawn in front of our dorms and opened the evening with Radiohead's well-known Creep.

Before we knew it, other ECLA students joined in and we all sang along to fellow student Andrei's guitar riff. The familiar sounds of Nirvana, The Cranberries, Damien Rice and Beirut could be heard all around and it was amazing to hear us all coming from different parts of the world and yet sing in unison.

Interestingly enough, some hidden talents appeared out of the woodwork and we had the good fortune to hear Selbin performing in Turkish and Jelena performing Serbian songs. There were even variations of the famous Smelly Cat song by some of the older ECLA students.

By the end of the evening, everyone had the chance to demonstrate their guitar abilities, just to make sure that we equally participated in this enjoyable mini concert.

However, that evening was not the end to the musical events. The following Saturday, right after finishing our first essays, the ECLA community went on to attend the concert of the band The Loafing Heroes - an extracurricular project of one of the ECLA ISU faculty.

The evening was opened by Daniel Dye, a country singer from Ohio. His show was a most welcome warm-up for the real pleasure that was to follow afterwards - the performance of The Loafing Heroes. Although not many of us were familiar with their music, their catchy tunes took us in and we all plunged into the ethereal sound of their music. The warm songs of The Loafing Heroes made all of us wanderers feel like we were coming home.

Finally, the cherry on top for the night was the lead singer's recital of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, accompanied by the calming guitar sounds in the background. This gave a completely different perspective of the famous T.S. Eliot poem and crowned the evening. As the night closed in around us, we truly felt like "our loafing had won".

And so it was that all of us felt prepared for yet another week of exploring the fragility and formidability of Prussian history. Only, this week is different. Now all of us feel like we truly belong to ECLA's community, because for those with whom you feel free to sing along with are people whom you can call friends.

Indeed, now we all feel the bonding powers of music. Music is magical, and so here and there between all those lectures and seminars, let's unleash a little more of that magic now, shall we?

HOMAGE TO HEINRICH VON KLEIST

August 10, 2011

Christine Toft (ISU'11, Denmark)

Reading Kleist's stories hurts, he stabs a dagger into my heart, I feel the world is wrapped in hopelessness, I feel paralyzed, and I feel something is true. Living can be a difficult task and involves mistakes, and this is brought painfully to life in Kleist's writings. The uncertainty of life is brought forth in Kleist's story, and it draws me in. I like the way in which Kleist is able to portray the fragility of social life, that law and order is man-made and that trust is a vulnerable commitment.

The curriculum at ISU features two of Kleist's works and an exhibition focusing on Kleist's life. Hence, I have been given an opportunity to work with a writer that I was not that familiar with. A previous encounter with two of Kleist's stories had started a fledgling admiration for him and during this summer course, the admiration has not withered but only grown stronger.

When Kleist was still living, his fame was limited; a lot of critics blame it on Goethe - the Godfather of German literature - who did not like his writing. To Goethe, Kleist's stories were destructive not devotional. Morality and security break down, death and destruction are omnipresent, and as a reader you sense that the next catastrophe is just around the corner.

Besides the all-pervading apocalyptic atmosphere, Kleist also stresses the unpredictable aspects of life. At the end of the day we cannot plan our life no matter how hard we may try. We can act but never predict our opponent's reaction; we can only guess and then act accordingly but guessing is dangerous - it might lead to mistakes and failures. Kleist is extremely aware of this and he offers no illusions about a world where it will be possible to prevention catastrophe and acquire certain knowledge - such a place is a utopia and those places do not exist.

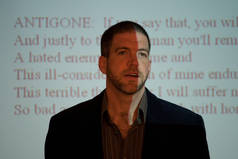

The Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote in his work "Poetics" that the most tragic is when misfortune is brought upon a common man not because of vice or depravity but by some fault on his own part; hence his fall is self-inflicted caused by an action with consequences he could not possibly have foreseen.

Reading "Die Verlobung in St. Domingo", one of Kleist's last stories, Aristotle came back to me. Deep down I knew the catastrophe was approaching, but a small hope that this might not be the case was nourished by the heroine's actions. Toni wants to save her lover and success seems within reach but all is changed because Gustav, the man whose life she fought for, misinterprets her actions and shoots her. It is so profoundly tragic because everyone else - the reader and other characters - know that Gustav is mistaken. Had Gustav only requested an explanation, had he only hesitated for a moment, this would not have happened. Alas, he realises this too late.

The bullet in Toni's heart makes everything irreversible. Kleist's characters live their life forward but can have no hope whatsoever of understanding what is actually going on before an event has taken place. Life can only be understood backwards - it is sad, it is true and can be very depressing. Understanding and insight always arrive too late and is therefore useless in guiding us through life.

On November 21st, it will be 200 years since Heinrich von Kleist committed suicide. He himself had faced the same uncertainty as his characters, he had realised that it was impossible to get to a deeper and truer understanding of the world. Kleist shot himself on the shores of the Wannsee Lake on the outskirts of Berlin and achieved the only certain thing in life: Death.

Death is the moment that puts an end to all uncertainty, where nothing more can be added to disturb the perceptions and interpretations of the world. When it comes the world stands still, not because we succeed in stopping it and get some perspective, but because we ourselves step out of the current of time.

Kleist's characters are caught in life and every action in life has consequences. When I think about Kleist's work, I really appreciated this aspect in his writing. He deals with the uncertainty of life in such a way that the reader is not left untouched. The characters live in the realm of uncertainty and this uncertainty finds its way into the reader's experience.

Reading Kleist, I will never be able to say: "This is what happened" or "This is true". I will never be able to make an interpretation that can contain the whole narrative or explain everything. I see the unpredictability of life in Kleist's fictional universe and I become aware that my own world - even though I have not yet found myself in a situation of complete destruction - somehow resembles Kleist's universe of fragility and velocity.

The uncertainty and unpredictability of life never goes away. This might be an obvious fact about life, and writing about it might be simple and unoriginal, but the fact is that Kleist makes it so powerful and vivid, and it makes me see further than before. His writing touches me, it strips me of my romantic, harmonious illusion about the world - and that hurts.

ISU VISIT TO REICHSTAG AND SANSSOUCI

July 20, 2011

Gjurgica Ilieva (ISU'11, Macedonia)

The second weekend of July marked the official beginning of ECLA's ISU. It was a weekend abounding in novelties with new students trying to get to know each other and going on two trips to kick-start the international summer university on Prussia: Philosophy, Rebellion and the State. What follows is an account of these two excursions.

In accordance with the topic of this year's ISU, the trips covered the period of German history from modernity back to the era of King Frederick the Great, Prussia's main proponent of enlightenment. You might as well have guessed, but it is still my duty to unravel the mystery and candidly state that we visited the Reichstag and Sanssouci, King Frederick the Great's summer residence in Potsdam.

The seat of the German Bundestag, the Reichstag, was built in 1894 and again reconstructed in 1999 by the British architect Norman Foster. It is an imposing building which stands witness to Germany's "long and winding road" towards democracy.

Starting in the main hall leading to the plenary chamber, our guided tour passed through several galleries featuring art works of different artists, then we went on to see the largely perplexing and open-to-interpretations chapel in the Reichstag, along with the drawers of all democratically elected MPs (even Hitler's). Passing by the walls inscribed with graffiti of Russian soldiers, we finally arrived to the plenary chamber to listen to a short but insightful lecture into German Parliamentary democracy.

Finally, we went up to the upper part of the Reichstag and climbed up the stairs of the glass dome, the symbol of transparency and openness. The "Dem Deutschen Volke" inscription simply confirms that the Reichstag deserved the title of "the heart of German democracy".

The following day, we made a leap in time and a change of track, and went to visit Sanssouci, the summer palace of King Frederick the Great. Located in Potsdam, the state capital of Brandenburg, Sanssouci was built between 1745 and 1747 in rococo style. Often times called the German Versailles, this palace is smaller in dimension than Versailles but much livelier in spirit.

As you walk from the Entrance Hall through the Marble Hall and the King's different rooms-dining room, study room, and a small yet well-preserved library, enlightenment seems to speak to you from the paintings and wallpapers, and the statues and instruments in all of these rooms.

Finally, we went outside to get lost in the endless green of the gardens and to truly experience the carefree spirit of this palace. Indeed, this palace of modest dimensions still carries a grand significance in itself, for walking through and around it, one can truly feel the refinement and splendor that was left behind by the Prussian Frederick the Great.

As the weekend drew to a close, all of us felt exhausted and awestruck in equal measure by the grandiosity of the two buildings. Not only do they hold a remarkable appeal for the ordinary tourist, but they also bear a great historical significance, which is of special interest for all ECLA students.

Personally, I was impressed with the idea of walking down the same corridors and galleries that were once inhabited by historically crucial figures in Germany. The heroes of history books descended into the real world and historical events unfolded one by one in our mind's eye.

It was probably that weekend that we truly understood that we have embarked on exploring a challenging, yet enjoyable topic, and we are looking forward to being "enlightened".

THE BRILLO BOX OF HISTORY

July 20, 2011

Mikhail Shakhanazarov (ISU'11, Kyrgyzstan)

The beginning never ended. Here we stand now and from here we move on. History has shattered.

I was brooding on this, when together with other ISU students, I went on a tour of the Berlin Museum of German History-a journey spanning over two thousand years of history, the living ashes of the Phoenix of human development, the twisted path of a nation, carefully crafted into an argument- "Wir sind ein Volk."

The central idea of the whole tour was to show the artificiality of history and its improper use as the objective representation of what has been, focusing on the room history allows for interpretation and humankind's tendency to transform it into a highly versatile tool - political, social, and economic. My goal is not to discuss the morality of the issue; rather, I will focus my attention on its necessity and meaning.

History is art. Just as a painter works with colors and obscures some aspects of a painting to shed light on others, so does the historian arrange facts, link together events into causal chains which he later uses to bind together a narrative. Lessons, dramas, joys, and tears - all of which comprise history, and none of that was really what it was. Just like any other art form, history cannot present an objective narrative. Still, just like any other art, it is based on a true story. This perhaps is an unconventional understanding of the concept, but it seems straightforward enough so as not to be too provocative or illogical.

What differentiates history from many other forms of art is its usage and creation. The Museum of German History is a very good example of the many ways in which history can be (and has been) used. It became very clear during the tour that the artifacts presented in the museum were arranged with much thought, and more importantly, with purpose.

As you walk up the staircase, a sign on the wall reads "The history of Germany, from the beginning to modernity." At the top of the staircase there is a beautiful Greek mosaic, and next to it, the gravestone of a soldier, fallen on the battlefield of Teutoburg Forest - the beginning of German history.

The very concept of the beginning of history can of course be argued to be meaningless, but in the art of history, the beginning is what makes the rest possible. It binds together the story of a nation, allowing the nation to exist, setting deep its roots and providing a background, against which its people are to stand out, united and unique. The very existence of a beginning is perhaps more important than its nature.

The beginning is established by historians. With a retrospective eye, they pinpoint an event that best suits the demands of modernity. At its root, history serves to make an argument and is focused on the present. As you walk through the museum, you see the story of the nation unfold. The Greeks, the armor of the fallen Turks, the towering Prussian generals, Napoleon - everything shows the history and greatness of Germany, but perhaps more importantly its unity as a state and a nation, defined through its culture and in contrast with its neighbors.

When viewed this way, history loses a large part of its value. Stripped off much of its romanticism by the almost cynical eye of an outsider, it shatters into individual destinies, into stories so small they cannot be seen with the naked eye. The causal chains of events break. The system crashes; we see a pile of chaotically tangled lives, and we wonder what chances there were of us coming into existence. This is history.

A QUESTION OF EXPECTATIONS

July 20, 2011

Christine Toft (ISU'11, Denmark)

"So, are you looking forward to going to Berlin?" my dad asked me the day before my departure. I thought about it, wanting to reply genuinely, but the only answer I could come up with was "I don't know."

Of course I wanted to go, but I wasn't like a little girl on Christmas Eve dying of excitement and impatience. Why? The thing is it is hard to build castles in the air when you don't know the base on which to erect them, and I simply didn't know what to expect. I had no idea what the professors and students would be like, and with whom I was to share a room - I could have looked her up on Facebook (common nowadays) had I known her name, but I didn't. I had seen a list revealing people's first names, many of them impossible for me to pronounce, and the only thing I could conclude from this was that this summer school would bring about encounters that I would not have had, had I spent my summer in Copenhagen.

Because of my lack of expectation, it is impossible for me to say whether or not my first week at ECLA can be classified as a disappointment or a success. I can only reflect on what it felt like, and it felt good. Actually, it was a bit reassuring because no one, with a facial expression of "I DON'T UNDERSTAND YOU!", asked: "Why the hell do you want to waste your summer away? What's so interesting about Prussia?"

Everyone is at ECLA because they want to learn and in one way or another, we all have some interests in common. Quite a few activities during our first weekend at ECLA helped to create a base of common experiences and got us to talk to each other because what are you supposed to do besides talk when you sit next to someone on the train, with whom you will be spending the next five weeks? Stay silent? That would be awkward.

The first days here were intense: the many new faces, the tours around Berlin, the many pages to be read - and all of these at the same time. I felt constantly divided between wanting to hang out with the people I was slowly getting to know and the knowledge that back in my dorm, there were hundreds of pages waiting to feel the presence of my attentive eyes, and this, I admit, made me feel a bit stressed. But now, as a daily routine has formed, studying here seems less stressful than what I'm used to, but that doesn't mean that I think the course will be a piece of cake.

The fact that everything is within a five minute walking distance, that all meals are prepared, that I only need to think about myself, my books and my laundry (ECLA has not yet hired someone to take care of this - too bad), has led me to the conclusion that ECLA is less stressful than what I'm used to - in a good way. ECLA is a place where I can devote myself 100% to learning, but I have realized that I will not only learn about Prussia, but also something about my own time.

For some reason I haven't thought about, before coming here, that I would be given an insight into different cultures and what it is like to be a student somewhere else in the world. Maybe I was just simple-minded, but now, after the first week, this intangible insight I got feels like a great gift, and I know that when summer is over I will be leaving Berlin enlightened in more ways than one, and hopefully I will also carry with me friendships that I couldn't have gotten elsewhere - those are my expectations for the rest of the summer. So I might have arrived without distinct expectations but now, with interesting lectures and good company, I have certainly got some.

SPRAY PAINT WORKSHOP

June 16, 2011

Milan Djurasovic (AY'11, USA)

On June 11, ECLA organized a spray paint workshop in which a group of students got together under the leadership of student Josefina Capelle and the professional artist Guillaume Cayrac, whose work can be found throughout Europe, to learn how to create a stencil template and employ useful methods for cutting it out, as well as to try out different spray painting techniques that are used on various backgrounds. With the newly learned skills, black gloves and a lot of protective plastic sheeting, ECLA students set out to repaint the red walls of the student party room with our own stencils and freehand images. I am happy to report that the final result of our perilous endeavor can only be described in one word, and that word is "awesome."

But before discussing some of the pieces that are now on the walls of the student party room I would like to first thank our guest, professional street artist Guillaume Cayrac for his great ideas and for sharing with us his genuine love for spray paint art.

"I was commissioned many times to make small, sellable pieces for a big amount of money, but I don't want to destroy the art," Mr. Cayrac commented.

Mr. Cayrac's love for his work was evident to all of us who participated in the workshop. With his enthusiasm, knowledge, and help we were able to transform the student party room into a work of art.

Making spray paint stencils is much easier than what one may think, provided that one has all of the necessary materials. Therefore, with simple instruction, even a rookie stencil artist is able to produce impressive work (as was the case with a number of our party room stencils). Step one of creating a stencil template entails choosing the image that one wants to work on. Not all images render great stencil pieces so choosing of a suitable image is an important and a necessary first step. For example, images that contain a lot of shading should be avoided by the beginner stencil artist because of their lack of visible contour lines.

The second step requires one to have basic computer skills, primarily photo editing, which is used to emphasize the contrast of the image. A strong contrast is preferable because of the confusion that sometimes arises in step three -- the tracing and the cutting process. Once the wanted contrast is reached, the image is projected onto paper and the contour lines of the object that is going to be cut out are traced. The missing or the cut out part will be the image of the final product.

If one is making a stencil of a face, which was the case for all of our stencils, one must be careful to leave little connectors attaching the facial features to the outside of the face so that the features do not fall off. And finally, once cutting is finished, one can proceed with painting.

The stencils that were created during the workshop range from Michel Foucault as a garden gnome to portraits of fellow students. ECLA students who have seen our final products know that I am not exaggerating when I say that the pieces we created this past Saturday couldn't be distinguished from professional work (mostly because Mr. Cayrac was there to correct our blemishes).

And finally, I couldn't end this article without mentioning the stencil that a fellow student Catalin Moise and I worked on. Our magnificent stencil is an image of Frank Faber, a restaurant owner/singer whose soul penetrating voice will not be forgotten by any ECLA student who dined at his restaurant during our winter trip to Braunlage. Frank Faber and the time I spent at his restaurant are very symbolic of my experience at ECLA this year. What Mr. Faber and ECLA have in common is their uniqueness. Both are charismatic, both are unapologetic about their ways (Mr. Faber allows his guests to dance on dining tables and he sports leather pants during his performances), and thanks to Stefan the Chef, both have provided ECLA students with delicious food. It is because of these reasons and many more that I will never forget my year at ECLA and my dinner at Mr. Faber's restaurant.

"AUTOBIOGRAPHICTION"

Month of Performance Art in Berlin

June 16, 2011

Aurelia Cojocaru (1st year BA, Moldova)

If someone had told me a year ago that I could participate in a performance art event, I would have been at least skeptical. I had always looked at avant-garde phenomena with a strange fascination, but this very feeling set boundaries. After having recently attended some of the events of the Month of Performance Art in Berlin (May), I am ready to declare that one, even if you identify yourself as a "mainstream" artist / thinker and these kind of happenings as avant-garde, the "mainstream" can only benefit from opening its eyes to the latter; and two, ultimately, how "avant-garde" is it? Perhaps, a century after the first "wave," we should stop labeling.

The fortunate event which reconfirmed my impressions happened at the end of May (thus, close to the end of the Performance Art Month), when I participated in a writing performance / workshop at Freies Museum, playfully entitled "Autobiographiction".

In anticipation of the event, we received some letters from the authors of the concept (which made everything sound perfectly abstract, I must admit, increasing the suspense). Thus, in Nicolas y Galeazzi and Joel Verwimp's vision (the latter being the organizer of the event here, in Berlin):

"Autobiographiction is a permanent workbook in constant flow of dissemination. In a chain-reaction of events it unfolds itself as shared content dispersing performance on paper. At the Freies museum it now will be handed over to all the participants. The methods of creating content, editing and disseminating are proposed by VerlegtVerlag. The tools were developed over the past months in Helsinki (Baltic circle festival), New York (apexart) and at the Roter Salon (Volksbühne Berlin). The archive will now be considered anew during the research session in an economy of mutual dependency.

Through a performative praxis, we hope to create a tension in the conceptual limits of research, mutating the way we appropriate space. This tension arises from recalibrating our own position which in the case of autobiographiction, departs from the archive XY in relation to the reuse and further development of VerlegtVerlag's objects and models. Locating this practice in a continuous dialogue between visual and performance art develops situations that frame the event by building a space that becomes VerlegtVerlag's speculative environment."

Having now confronted you with just a fragment of the whole conceptual construction (It does sound quite abstract, doesn't it?), let me tell you what factually happened (although the philosophy of the event is to precisely erase the limits between appearance and reality).

Over the course of one day, people freely enter a wide white room in the museum, in which the only pieces of furniture are 10 or 12 chairs and, somewhere in the corner, a small table with a suitcase and a box with folders. You choose a folder or an object from the "archive." For the next two or three hours (the moment you stop is completely arbitrary, in fact) you will talk in a quasi psycho-analytic flow about your own biography, but provoked by what you actually find in the folder. The other(s) will write it down, filtering this again through their own vision. Or vice versa: you will be writing while the other(s) will be talking. It is less important (less obvious) how the constellation of individuals is arranged. What is really important (more obvious) is the final product: a complex, multi-layered biography of a fictive individual Z, which somehow encompasses the identities of all those Xs and Ys who have, at some point, contributed to the "narrative". Interestingly, the two artists who initiated the project possess each other's archives. Through these kind of events, they are, in fact, writing and rewriting each other's biography. But, because of the multitude of "rewriters", these could no longer be simply biographies, but rather, as the title suggests, autobiographictions!

Needless to say: what this does to the ideas of biography and authorship is simply hallucinating. This so called (by the authors) amorphous authorship (or agencement) simply annihilates any boundaries between the initial owners of the archives (the two artists selecting specific moments from their biographies), the secondary owners (the two artists "managing" each other's biography) and the tertiary authors (those who, through re-writing, include their own biography in the equation). The outcome is neither more nor less than a "colonial" identity. Plus, it is not clear when the two artists will actually stop rewriting and tie together all the threads of this new biography of Z, this child of fiction (at some point, the materials produces by the participants at the workshop(s) could themselves be used as starting points).

Ultimately, I'm not sure that actually that mysterious Z hasn't changed my own biography. The reason why I say this is that, from the pile of folders, I chose one which had a map. Strangely, the map contained an itinerary which, by coincidence, I had also undertaken. From the very moment I saw this, all abstractions and equations collapsed. By talking it through and writing it through, my life was simply happening.

LEONARDO'S ART

June 16, 2011

Maria Khan (AY'11, Pakistan)

If a painting is presented to two people, each of them would probably see something different in it. They might even disagree about what they see to the point of drawing daggers. Art involves the viewer in a very unique way and the experience of looking at something and feeling something is individual. As we study Renaissance art this term, we look at how objective or subjective this art is, by analyzing the different methods of drawing used by artists such as Leonardo da Vinci over the course of history.

ECLA invited Dr. Frank Fehrenbach, who is currently living in Italy, on sabbatical leave from Harvard University, to give a lecture on basic questions related to Renaissance art. His lecture focused on various aspects of Leonardo's art.

He started his lecture by describing the 16th century art period as a "revolution within a revolution." He went on to describe that the revolution of three-dimensional art had started during the 13th and 14th centuries - the early Renaissance period during which artists began depicting images in a more human and real way. The 16th century was a step further in the direction of naturalism and realism. The beauty of 16th century art lay in the way it was painted to involve the viewer in an extremely inclusive experience. It defined the methodology of art and influenced later art. We would now take techniques of perspective as a given in modern art, in the same the way we take the solar system for granted, but at the time when this technique was discovered, it was revolutionary.

Leonardo, as Dr. Fehrenbach put it, changed the meaning of reality and 'natural'. He started his study of art from the inside of the object and went on to paint the outside as well. Dr. Fehrenbech showed the drawings Leonardo had done in preparation for his work and explained how those drawings showed the inner workings of his mind. He showed us how the drawing clearly dealt with each and every minute detail of the work with the intention of showing the very way the actual thing would be. In as many words, Leonardo made people see the reality for what it was and the way he viewed it. In his work, there is a play with the idea of objectivity and subjectivity.

Dr. Fehrenbech also very clearly laid out the autobiography of Leonardo and linked it to his process of creating works of art. It was a surprise for me to know that as a child Leonardo dropped out of high school, which would never allow him to learn Latin, Greek, and Mathematics. Yet, his genius was indubitable when it came to creating highly technical equipment for war or for the city. He also identified himself as an engineer and not as an artist in a letter written to a ruler of that time, when offering his services to him. Leonardo produced unlimited works of art during a very short period of time, but he embraced his artistic side in the most difficult and psychologically depressing periods of his life. When he struggled most with his work, he produced the best art known to mankind.

Dr. Fehrenbach's lecture highlighted some of the most important aspects of Leonardo's art techniques and the message to take home was: what exactly is reality and nature in Leonardo da Vinci's view?

EUROVISION SONG CONTEST 2011

(Or what does Europe want?)

June 2, 2011

Aurelia Cojocaru (1st year BA, Moldova)

Although I promise myself, each and every year, that I will stop watching the Eurovision Song Contest (ESC), this annual moment of laughable grief (meaning that the initial enthusiasm that accompanies some of the songs is ultimately destroyed by the final results), I always end up doing the opposite.

2011 couldn't have been the year when I actually kept the promise. First of all because ESC had "come" so close (Is it following me?!?). The events took place in Dusseldorf this year, after Germany's victory in 2010. Second, because thanks to some of my colleagues' initiative, a screening of the final show, which took place on the 14th May, was organized in one of the dorms, so that we ended up sharing in the convulsions and the blubber of that night of self-exorcism that Europe seems to perform every year. A night of "snacks and circus", I would say (I myself chipped in with some "thematic" fruit jelly Euro cents.).

Our fellows from the other continents (those who, hesitantly, joined us) couldn't at first understand the cause of our bizarre excitement, but once the show started everyone entered the frenzy, not to mention the treat that the voting process, the famous douze-points-giving, was.

I won't make extensive comments about the songs (be it for the fact that I was bound to have a favorite), but I will say that, just as it does every year, Europe came onto the stage well-adorned, with strange hairstyles and straining voices, covering, as usual, a most hallucinating span of genres (even opera counts, with France as an example). Europe sang in English, sometimes even in macaronic English-French (like Lithuania). Europe brought on the stage dancers, actors, and other celebrities just to make the performances "fuller." Eccentric decors and letters-on-jackets forming the name of the singer (see Russia's performance; memorably, in 2008 they won with Evgeny Pliushenko on the stage!). All this, combined with the gigantic screen projecting parallel motifs, made it vertiginous.

One couldn't find time to comment upon everything concomitantly. The experts in art focused on the visual effects (Greece had hip-hop elements, with ancient columns projected on the screen!), others detected here a crystal Celine Dion voice, there a false note, but ultimately most of us were part of a strange "yes or no" spontaneous jury. Whenever the representatives of one the countries whose natives were among us performed, everyone clapped and was merry.

Merry-go-round as this all is, one gets the strange feeling that nothing actually changes, as years pass. It's a carousel. Every year you could trace this or that underground relation to a previous contestant or song. Every year-the persistent beginners, then, some ex-pop-stars trying to resuscitate their glory, then sometimes winners coming back as if craving a failure (The German winner of 2010 obeyed this logic and participated this year.), sometimes those who didn't make it the first time winning on their second try, and so on.

There is even an "ESC style" of music, which one immediately recognizes. Although it's not always the case that this guarantees victory (and that's when rock, for instance, takes over the unadventurous pop, eventually with some ethnic vibes).

But all this showbiz swing doesn't really mean anything without the usual political controversy (i.e. the final vote). It is enough to say that some call it all "Neighborvision".

We ourselves came to the conclusion that there's no better way to understand Europe and its (political) climate than to look at how each of the countries' votes are distributed. Thus, following the well-known logic, the Balkan countries will support each other. So will the ex-Soviet countries. On the other hand, it's no surprise when Moldova exchanges twelve points with Romania, Greece gets its twelve from Cyprus, and Italy from San Marino, etc.

Whenever an exception to the rule happened, everyone was electrified. Iceland and Hungary amazed everyone with their incredibly "diverse" votes. Or what about Israel voting for Sweden (after a more or less recent diplomatic conflict)? The question was, each time: Is country X making a political statement by giving fewer points to Y this year?

We can only hope that the exceptions (not few, I guess) prepare a more non-political Eurovision. But I also couldn't help being disappointed at the end. Alas, it's the last time I will watch it (I promise)!

All in all, there was too much of Europe in Europe that night. A paradoxical unity, I would say (the organizers decided to "celebrate" it by making the intro video for each country . . . a portrait of an immigrant.). Now that we know the winner (Ell/Nikki from Azerbaijan - "Running Scared"), we can ask ourselves: What kind of music does Europe want and why? Ultimately, what does Europe want?!? Europe wants, in torturing "adoration," to "run scared tonight." And also Europe wants to . . . imperceptibly glide. To Azerbaijan.

WELCOMING STEFAN THE CHEF

(Or Culinary Tales and Theories My Mother Taught Me)

June 2, 2011

Milan Djurasovic (AY'11, USA)

"You better learn how to cook or your life will be solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short," was what my mother's advice sounded like four years ago before I left home for college. Despite being a big fan of Thomas Hobbes, my mother prepares the most delicious food known to man. Her food is not extravagant and she doesn't add any herbs or spices to her dishes. The only additive that my mother uses to transform the everyday ingredients into pure finger-licking deliciousness is love.

However, I dismissed my mother's wisdom primarily because I was developing my "sandwiches are sufficient" theory, in which I claimed that a variety of sliced cheese (e.g. some of the Amish classics, such as Brick or Provolone) along with sliced Fegatelli or Milanese salami placed in between two pieces of toasted rye bread that was previously smeared with cultured butter, would be an adequate diet for any college student. Unfortunately, my theory was discredited then. And again a few weeks ago, when I decided to re-test my old theory while waiting for Mr. Stefan Will, ECLA's new chef, to arrive and take my food worries away. For three weeks I lived on sandwiches and yogurt, and with each Skype conversation that I had with my mother I was reminded of both the soul-crushing and repeated failure of my sandwich theory as well as my protruding collarbones and my thin wrists.

And then came the morning of the 9th of May, a morning that I will remember by hot coffee, five or six different kinds of bread, and by a stabilization of my bowel movements. As I was about to bite into my fresh and crispy croissant, Mr. Will came over and cracked a joke or two which made coffee come out of my nose. We laughed about the coffee incident, patted each other on our shoulders, and I thought to myself: "It's been a long time since I felt this warm and fuzzy on the inside." My joy was further expanded when for three days in a row there was at least one potato option for lunch.

In the small, Christian Orthodox town in Bosnia that I spent my childhood in, potatoes were praised and celebrated with same fervor as God himself.

"Life is meaningless without potatoes," my grandfather would often say as he cut the local "Torotan" cheese to eat with his boiled potatoes.

In fact, boiled potatoes and "Torotan" cheese were exactly the ingredients of the sturdy foundation that kept my grandparent's marriage intact despite their poverty, countless doubts, and constant bickering. As far as I can remember my grandparents spent nearly all of their days squabbling over the pettiest issues. For example, whenever my grandfather left his dirty clothes on the bathroom floor instead of putting them in the basket, my grandmother felt that her husband was walking all over her and disrespecting her in the most despicable way. The act of walking was also a frequent topic of their quarrels. My grandmother always whined about how my grandfather walks too fast for her and she believed that the purpose of his speedy steps was to get her to walk faster as well. It is true that whenever my grandparents walked somewhere together my grandfather would walk about two to three meters in front of my grandmother and she hated this because she needed to yell every time she needed to tell him something.

"My Hercules can't even hear me when he is right in front of me," my grandmother would complain to her friends, "but he just speeds in front of me as if he has somewhere important to get to."

The only time of the day that my grandparents spent in peace was during dinner while they peeled and ate their boiled potatoes. Every night, for fifty-two years, my grandparents have eaten boiled potatoes with cheese, and every night at seven o'clock while their mouths are filled with mushy potato deliciousness, my grandparents gaze into each other's eyes and flash their smiles of satisfaction which convey to each other that it was worth sticking together for five decades. Who would have known that the secret to creating a strong and enduring relationship is found in boiled potatoes? Trust and understanding can keeps the couple's union firm only up to a point but the power of properly baked potatoes takes hold of the lovers' souls and enmeshes them together for the eternity. With the last reminder about the importance and deliciousness of potatoes, I would like to welcome our new cook Mr. Stefan Will and his employees to the ECLA community and ask them to keep up the good potato work.

TWO LOVES

June 2, 2011

Maria Khan (AY'11, Pakistan)

We spent the whole of last term talking about love and the many different ways it strikes us. Coming from the East, I was introduced to a whole different set of values associated with love and its manifestations. A very basic observation is that in Eastern cultures when people fall in love, they avoid public displays of affection whereas in the West these displays are a norm which strengthens the bond between two people. My close study of love in the Western tradition made me see the differences between the West and the Orient in the political, social and economic sphere.

C.S. Lewis talks about four different kinds of love in his book The Four Loves. By closely reading the text along with Plato's Symposium, one understands that in the Western tradition love is not only a source for sexual mating between two lovers but it is also a tool used for transcendent thought. A very big misconception which rests in the Eastern tradition about Western cultures is that relationships in Western cultures have lost their value because of the presence of pornographic media. But one is pleasantly surprised to read about the sacred concept of love present in Western literature.

Love, as described by C. S. Lewis, can exist between friends, acquaintances, and lovers. It can also exist in the form of 'agape'. Agape, or Charity, is practiced by human beings for the love that people have for God. The ultimate message of Christianity is to love and serve your life by helping each other.

The question which a Saracen or a non-Westerner asks while living in present day modern society is, where do you see or feel this kind of love that is being advocated in the Bible and some ancient texts. Do people actually look for transcendence when they fall in love? What effect does this kind of love have on the modern day Western liberal democracies? The answer to these questions can be a long and hard one but on some investigation I was able to craft a response, which satisfied me and hopefully will do some justice for my readers as well.

The contribution of Western societies in the field of knowledge has been very significant; one of the most distinguishing contributions has been the methodology of research, which was unknown to the world. Although the ancients contributed a lot in various fields, their ways of conducting research were not very well refined. Research techniques were something which mankind still had to discover and establish. Research as a practice, requires the subject to study the object in such great detail that he has to be immersed in it to find out in great depth what that object is and what value it holds in the modern world. This practice then gives birth to new ideas emerging from the old one established. It is in the same way that Copernicus was able to refine the then known information existing in the world.

The point that I made at the very beginning of this article was that love and research are very closely connected. The concept of love asks you to honestly and sincerely dwell on something, to get married to it and devote your life to it. This kind of devotion not only promises transcendence, which students and professors together experience in universities and learning centres in the West, but also plays a huge role in the development of the society.

An important factor to note here is that although Western civilization has achieved remarkable success in the area of knowledge, they paid a very big cost for it -- the cost of family life. The life of a Westerner is so fast-paced that it is impossible at times for him or her to acquire a normal balanced family life. Often times, my Westerner friends would even laugh at the concept of me planning my marriage, while I should be only focused on my career and academics. I admit that my marriage or family responsibilities change the dynamics of life, but the important question to ask is, how happy will I be with all the important qualifications and career moves? Is it not important to have human beings as your prime motivation for success in your life? This is something that Eastern societies do not miss: Family.

The Eastern lifestyle promises a lot of comfort and genuine love, which families and communities enjoy within them. The concept of love in the Eastern tradition does not consist only of what comes from the Islamic tradition. Chinese and Indian traditions have also played a huge role in shaping that concept. It goes beyond the scope of this article to discuss the details of love as a metaphysical or social concept within each of these traditions.

But one thing that Eastern societies have achieved is a great place for human relationships and bonding. Something that is considered a waste of time in the West, would be considered mere selfishness in the East. My friend Oumaima Gannouni would be witness to this dichotomy. In the East, everyone has time for everyone. Neighbors, family members, parents, and siblings - all are overflowing with love and support. This network of support and love actually plays a very big role in shaping healthy minds and bodies. Stable marriages breed stable souls. It is a divine comedy that although you find these minds in Eastern societies, the lack of opportunities and infrastructure does not give them an opportunity to outshine. Part of the reason why there are fewer opportunities in the East is because people lack a sense of proportion when it comes to emotional ties, which then leads to easy going behaviors and less efficiency. Moderately governed emotional ties actually breed very useful minds, which then are transported to the West in the form of a brain drain.

The two different forms of love that govern the world, contribute in different ways. It is now important for social psychologists and philosophers from both worlds to sit down and think about various ways to cut down the cost which development has brought in the Western world. The world would be a Utopia the day that both elements could co-exist simultaneously in the East and the West.

POSTCARD FROM NEW YORK

May 20, 2011

Snezhina Kovacheva (ISU'05, AY'09)

Dear ECLA,

This is to proudly share I graduated from Columbia this weekend. The ceremony was outstanding, with an inspiring speech by Kofi Annan. The speech is here.

I would like to thank you for my time at ECLA before Columbia. While I have undoubtedly learned a lot this year, it all fell in place onto the foundations that ECLA built. I swept through challenging assignments with a confidence that can only come after having done the kind of thinking that only ECLA can put you in the position to do. I committed the usual sins of an ECLA graduate - I often found myself asking questions with the word "values" in them, persistently inquired about the ultimate goal, thought about social justice, and had the courage and eloquence to disagree when I didn't see important considerations involved in a discussion.

It has been a long road, above all metaphorically, from when I first started at ECLA's international summer university. I still remember talking to Thomas Norgaard about PY vs. AY and wondering what will come at the end of a semester dealing with Plato's Republic. Somewhere along the way, I forgot about the journey's destination. And this is when my real journey began...

It is not completed yet, and I am ready to embrace it as a life-long process. I am still not sure what exactly I will be doing after Columbia. I know I will be coming to Berlin and ECLA on Monday, and spending a week in Berlin. Over the last three years, a few apartments, rooms, street-addresses, cities and countries have been changed. But my spiritual home remains fixed at Platanenstrasse 24.

All the best from New York,

Snezhina

THINK ALOUD OR DEBATE

May 20, 2011

Maria Khan (AY'11, Pakistan)

The art of speaking is hard to master.

It is with the intent to master the art of public speaking that I began my debating career almost three years ago in Pakistan. Slowly and gradually I climbed the ladder of public speaking. It was right after I had achieved a big break in debating that I came to Berlin and found myself in one of ECLA's seminars, dumbfounded and numb. The article below will reveal a lot of the things I discovered speaking and expressing myself in the seminars and as I started debating with the Berlin Debating Union.

ECLA seminars demanded extreme honesty on extremely difficult and demanding texts. Not only was seminar participation focused on your input about a certain text but other people's ideas and questions instigated one to participate. It took me some time to understand the actual meaning of this participation and I struggled to speak my heart and mind about philosophers I esteemed. I was so scared having never meddled with them so casually before. I was also learning what it meant to engage with a literary idea with all your heart and soul. The peer pressure was humungous. Initially everybody noticed your way of speaking, what you had to say and the recurrent theme in your questions and ideas. In close quarters, everyone discussed each other's way of speaking. Some people were permanent favorites and others marred for good.

I questioned my own ability to talk and present something in public. Back home, I had received a celebrity status in my own college for my talents in oratory delivery. But who knew that an ECLA seminar would be just a lot more than speaking and presenting your ideas. As I was struggling to acquire a firm grip of this methodology I came across the Berlin Debating Union and I started debating with a group of people passionate about world affairs and debating itself. It was a classic case of going from theory to practice. Where in a seminar I was learning to speak from my heart, in parliamentary debates I changed my approach towards speaking and I brought the two worlds together, to much benefit.

Every Tuesday night before the motion I stood. Even now as I stand, saying "This house believes that . . .", I force myself not to just reproduce what I read in the Economist. Instead, I do what we all do in ECLA seminars: emotionally, spiritually, and rationally associate with the text.

In the beginning this resulted in me being unable to deliver a speech during several debate sessions, as I was trying to focus very hard on what the topic meant for me. But as time passed and as my fellow debater friends have witnessed, my debating skills have become much more refined and sophisticated. As I travelled to attend some debating tournaments, I saw what superficial and bad treatment scores of debaters gave to the topic at hand. Whatever they had learned through bits and pieces of news, they would puke out in the seven minutes they would get in the debating match. The seminars at ECLA had helped me so much, as I was passionately able to associate myself with what I was speaking. Not only that, I was able to deeply analyze a topic which remains the prime concern of any good debate.

The challenge that I faced in the form of preparing for ECLA seminars helped not only in getting reasonable grades, but also helped me in refining my thought process and the understanding of the subject matter as a whole.

"GOD IS DEAD." LONG LIVE GOD?

The "Future of an Illusion" Foretold

May 20, 2011

Aurelia Cojocaru (1st year BA, Moldova)

On good authority, I know that many of the people who came to attend Julia Kristeva's lecture ("The forces of monotheism confronting the need to believe") at Haus der Kulturen der Welt on March 8th, did so me more for the speaker than for the subject as such. And how could you not get excited? As "Mrs. Structuralism" came onto the stage, I myself thought there comes a time when the idols from the textbooks descend into the real world.

But this is not to say that the lecture itself didn't promise to be at least intriguing, if not controversial. Let's take a look at the title, for to me it sounded like a bundle of contradictions. On the one hand, of course, you wouldn't expect an expert in psychoanalysis to preach, but why then the title, "the need to believe"? And how do the "forces of monotheism" (anticipating, in a way, broad references to "the genius" from Freud's Moses and Monotheism essay) "confront" it? So, the very forces of monotheism oppose the belief?

Not to take the speculation too far, I'll mention that right from the beginning of the lecture Kristeva struck a somewhat balanced position between all of these possible contradictions. It's a "new approach" that Freud constructs. Psychoanalysis just sets "question marks," not "truths" (Kristeva takes a prudent step here, were it not undermined by extensive and confident references to the "genius"!). What post-Freudian figures such as Lacan and Lévi-Strauss, along with proponents of feminist-inspired movements, do is to simply add new meanings to the "question marks." For instance, Lacan's definition of the "symbolic" is derived from the incest taboo whereas the feminists' attempt to "deconstruct" the monotheistic through meditating and researching such areas as motherhood.

Ultimately, in Kristeva's view, the major discovery that psychoanalysis made was "the Other[ness]," or the idea that "belief" is first and foremost that which enables human connection, communication as such.

So the six themes which were developed in the talk (alas, Kristeva never got to the last theme due to lack of time) departed from the idea of "believing and knowing" as seen by psychoanalysis and continued with the hermeneutics of religious texts (focusing on how "the subject in man" is born from "taboo and sacrifice" in the Bible), just to get to the idea of the father-son in Christianity (which seemed to be the backbone of the lecture). Skipping references to Islam (namely, a discussion on "Islam and the problem of murder"), the lecture ended in a dilemma, broadening into issues of "secularization and cultural diversity." The last part made not only an enquiry into the possibilities of psychoanalysis to shape our future within the monotheistic foundation, but also a whipping summary of intellectual history.

Perhaps one of the most interesting shifts that Kristeva mades with respect to the paternal figure within the psychoanalytic view of human development was in seeing it initially not as an authority figure (with which one identifies, through what Freud called "primary identification"), but on the contrary, as a source of the "confident recognition offered by the father-who-loves-the-mother and is loved by her." This kind of identification with the father triggers utterance.

"I believed and therefore I have spoken" (Corinthians II, 4:13) - this seems to be, in Kristeva's view, the parallel between the one who has faith and the child making his first "steps" in his linguistic development. This moment of identification not only teaches the child the lesson of otherness (i.e. that the child is "other" than the mother), but also marks the beginning of a long, we may say endless, struggle: knowing.

To what Lacan considered the motto of psychoanalysis "you can know," Kristeva confidently adds, "if you believe." Psychoanalysis, in its practical, curative form, should also function according to this principle. Could, then, this mode of experience within psychoanalysis "save" us from the "death drive," as Kristeva affirms?

But how far can the omni-efficiency of "Other[ing]" be taken? I ask myself. In our speaker's view, the Bible reconfirms and extends this phenomenon: through its dichotomies (pure/impure is one of the most important) and through the privilege of taboo over sacrifice, the Bible sets up the necessary "gap" between the Other (the Creator) and the human being. What Judaism obtains through its emphasis on taboo is more than fear of God's abomination; it is "the emergence of the subject in man." Seen from this perspective, the existence of the state of Israel is neither more nor less than an "anthropological necessity."

It's because of the persistence of taboo that we leave behind this loving paternal figure and the "path is thus paved in the unconscious for the Oedipal father." What about the relation between Jesus and the Father? Kristeva asks us to observe in the figure of the former not only the "beaten Son," but also the "beaten Father." This enables "virile identification" with this figure, which becomes an "ego-ideal." Briefly, the incest taboo is symbolically suspended with this "association" through suffering -- suffering which is necessarily experienced as "marriage." The sublimation of the prohibited desires thus can only happen by acknowledging them. The way to a new kind of suffering ("divine," "Christic") is paved: it is not pure Law and guilt that composes the substance of the religious feeling now, but "jouissance in idealized suffering." This ultimately only encourages "symbolic activity" (since sublimation of these sadomasochistic tendencies triggers aesthetic representation).

What, then, does secularization change? In Kristeva's opinion, it is not only the universal phenomena observed by psychoanalysis that still function within the subject (Note that the emphasis is on the subject formed within the Greek-Jewish-Christian tradition.); similar to the redefinition of the Oedipus complex within this tradition, "modern secularization" treats the transgression of Law as "invitations" to create "new legalities." Surprisingly, Kristeva extends the influence of psychoanalysis to the subjects developed within different religious traditions. Globalization itself imposes psychoanalysis. What assertion of the universality of psychoanalysis could be stronger than the confidence that it is "beyond the clash of religions," that, in a secular "context," it can "reflect on all traditions." This is justified simply because the "need to believe" is "a pre-religious and pre-political anthropological necessity" (that is also to support for instance, Hanna Arendt's view, namely that "turning back to religion" for political reasons is not an option). The result could be, we intuit, a middle path between religion and "extravagant freedoms," between the "course" and the "broken course." Turning again and again to the Jewish tradition, Kristeva stresses the "dignity in difference" which the meaning of Akeda/the sacrifice (see Genesis 22) conceals.

To the "normative" and "critical" forms of "Jewish modernity" (the latter seen through the figures of Kafka, Walter Benjamin, and Hannah Arendt), our lecturer adds the psychoanalytic perspective (with respect to religion, it can mean a serious "re-foundation" which modernity definitely encourages). Kristeva identifies the rupture with the "mythic past" at two crucial moments: the birth of Christianity and the Enlightenment (with "seeds" in Baroque); but it's not only "cutting off" tradition that is here at work, Kristeva claims, but a deep need to "recreate," reshape the foundations. As Freud himself seemed to imply in Civilization and its Discontents, the discovery of the unconscious by psychoanalysis is another such leap into a new kind of modernity. Facing "today's conservatisms and fundamentalisms," only this "analytical" modernity could help us in re-linking "normative" modernity and "critical" modernity. This is the path to "refoundation" and it could be applied, the speaker is confident, not only to the Judeo-Christian situation (observing the model as such means understanding how "mutations" within modern religions happen).

I ask myself, together with Julia Kristeva who asks herself, whether she is not "too optimistic" about this possibility "to reinvent/recreate a refoundation?"... But I can't help being sympathetic towards the idea that monotheism is ultimately capable of reinventing itself and that the religious phenomenon can be more than a story about obeying (i.e. the need to believe and punkt) but also a story about "knowing."

ECLA IN KYRGYZSTAN: A TRAVEL DIARY

May 11, 2011

Gabriela Ionascu (PY'11, Romania)

On April 27 Madalina Rosca, Sarah Junghans and I journeyed to Kyrgyzstan to attend the international student conference on Freedom and Responsibility organized by the American University of Central Asia (AUCA). Although free, responsible and legally aged, we didn't go alone. Bartholomew Ryan and Bruno Macaes also came, to offer us their support, and nonetheless a bit of their expertise.

Given the fact that we arrived two days before the conference started, we had some time to discover the beauty of Bishkek and its surroundings. And so the adventure began…

Following Bruno's suggestion, we decided to rent a cab and to visit the famous Issyk Kul Lake. It took us four hours to get there, four hours in which some of our talents and interests have been revealed. Thus, we discovered Madalina's hidden talent for Russian language- she was the only one who could communicate in Russian with the taxi driver Stanislav who didn't speak English, although we all ended up having no problems understanding each other by the end of the day. There was one mercurial Russian word "remont" which remained the word of the day that seemed to be applied to everything. Bartholomew equally amazed us with his curiosity in the politics of Kyrgyzstan and his ambition to learn the most necessary Russian words ('privet', 'kak dela', 'spasiba'- he even took notes!). Speaking of Russian language and culture, Bruno has discovered that he likes music after all. He showed a real interest in the radio "friendly" oriental rhythms and an authentic passion for the songs in Tolstoy's language. Our trip didn't stop at Issyk Kul. We made sure that we didn't miss one single place of worth around Bishkek.

On April 29 the conference commenced. An enormous, scary room with stage, microphones and lots of seats welcomed us. Fortunately (or unfortunately for our teachers) we didn't have our presentations there. The organizers of the conference prepared us two cozy rooms, ready to encounter our flourishing dialogues. During the two days of the conference, the small ECLA group had the opportunity to exchange ideas with students and teachers from Bard College (New York), Bratislava International School of Liberal Arts- BISLA, and AUCA. With different perspectives and arguments, the students reached the same conclusion: social and political participation do count and one individual can make a difference.

Our adventure didn't end with the last speech of the conference. On April 30 our wonderful and gracious hosts Makhinur, Mary and Jamby from AUCA organized a traditional Kyrghiz feast in Ala Archa National Park. In a small yurt we enjoyed a piece of the fabulous Kyrghiz culture: from paloo, horse meat, and kymyz to folkloric songs about shared and unshared loves. Animated by a genuine desire to discover the surroundings, we got in the middle of a traditional race. Even though we didn't understand the tradition of the game, the rules seemed pretty clear: first, the one who runs faster wins, and second, the young women should compete with the other young women, elderly men between them and so on and so forth. The moment Bruno saw the contest, he knew that it would be a great occasion to teach his students the true meaning of competitions. Without hesitations, he ran to compete with the elderly men. Although his result didn't classify him among the best mature runners, he taught us that competitions are not only made for winning. Bartholomew equally joined the race. This time the lesson was different. ECLA students should not be afraid of competitors and try to do their best. For this purpose, he decided to compete with the young men. Life is not always as in movies, so Bartholomew's result was not the winning one. If you, my reader, are disappointed that ECLA had no champions in Kyrgyzstan, let me tell you the story to the end. Sarah and I got involved in the competition as well. In spite of my efforts to get the Kyrghiz start signal and to keep my dress in a decent position, my performance didn't equal the one of Sarah. Despite having missed the start, Sarah ran faster than everyone else. She was simply unstoppable.

After the race and a well-deserved Kyrghiz dessert, we went back to the hotel. We needed to get ready for the trip back to ECLA. On 2nd of May, we were back in Berlin, a bit more responsible and freer.

A TRIP TO REMEMBER

May 11, 2011

Maria Khan (AY'11, Pakistan)

One of the biggest attractions of the academy year program is the Florence trip, which takes place every year before the spring term starts. The trip to Florence promises a very extensive education on Renaissance art and architecture interspersed with a glimpse of the political and historical ramifications of those works of art.

When I came to ECLA, students who had attended the program the previous year fed me their anecdotes about what Florence was like and what they did. Nothing of that reappeared except for the physical structure of the city itself.

The Florence trip is a cut out of ECLA's usual time frame. It places you in another framework altogether -- with different parameters of academics and relationships. During the one week that I spent in Florence along with 30 other students and professors, I strongly felt the changing dynamics of our relationships with each other and with knowledge.

For the first two terms, we studied the meaning of justice and what Socratic education is like. We also looked very deeply into how we understand the notions of love and passion. The last string in the series of knowledge was to see how art and architecture bring forth the complete understanding of what knowledge is and how we as human beings relate to it.

In trying to understand the creations of Ghiberti, Donatello, Raphael, and so many more artists and architects we closely observed the creation of knowledge and its manifestations in great pieces of art. With aching feet we stood with art historians and our professors, trying to absorb the meaning of creation, a process that will in turn affect our ability to create something in the world in which we operate today.

My dire question as to whether the philosophical training that we receive at ECLA is useful or not was also gradually answered. In a candid discussion with Peter Hajnal and Jakob Dreyer, we all agreed that philosophical education enhances peoples' ability to contribute to the world. Philosophical education does not just consist of some big ideas that appeal to us on the basis of their popularity. Rather, it helps us to create by providing us with foundational ideas, just as philosophical ideas were the foundations of creation in the Renaissance.

On a lighter side, during the Florence trip, we already began to see new musicians cropping up. The Waldstrasse Boys made progress on their new albums and made the trip ever so joyful.

Not only did this trip help me engage with the creation of knowledge in such a genuine and honest manner but it also made me see the new developments in our interpersonal relationships. It would not be wrong to say that at ECLA we all exude very high level of energy. Relationships are intense and meaningful. We all tend to bring energy from the seminars into the dorms. The spirits of learning, competitiveness, admiration, and jealousy, all seem to co-exist at the same time. Our very beings, however you might interpret "beings," develop in various dimensions, due to the many ways in which we relate to one another and the various texts we read.

Art also helped our beings to expand. We were able to absorb a deeper sense of each other by engaging with the pieces of art that we looked at for hours. Michelangelo's nonfinito sculptures raised questions about the ideas of perfection and imperfection. Nobody knows what perfect is. Sometimes a half finished piece of art can be considered perfect and give that artist a legendary status. For me personally, a certain kind of humor that sometimes seemed condescending now appeared more human -- special courtesy to Anna Krasztev-Kovacs and Jelena Barac - as a result of understanding the ambiguity in the notions of human perfection and imperfection.

Art did wonders for me. As we reached Berlin with aching feet and bones, our minds and hearts were fresh as ever and the spring term welcomed us with open arms.

DYNAMICS OF MODERNITY

May 11, 2011

April Matias (1st year BA, Philippines)

A week's worth of immersion in Renaissance art requires both time for contemplation and occasion for discourse. As such, the spring term's core course on Values of Florentine Renaissance commenced with a guest lecture by the prominent Hungarian philosopher Agnes Heller.

Professor Heller broached the topic of historical interpretation by briefly discussing Goethe and Hegel's views about the Renaissance, particularly the view that the primary concern during the said period was beauty. Professor Heller carried the idea further by saying that the Renaissance's preoccupation with beauty is one of many expressions of a greater development, which she called the dynamics of modernity.

These dynamics manifested themselves in the processes of questioning conventions, standards, and traditions, and of searching for answers, which eventually burgeoned into an all-encompassing social movement. In time, the individual stepped into the spotlight and developed into a creature of choices. The application of knowledge and improvements in technology only served to amplify these changes.

Professor Heller looked to Giotto and the discovery of perspective in painting as fitting examples of these changes. Perspective endowed works of art with a sense of stylized reality, wherein seeing in painting tries to emulate seeing in everyday reality. The technicalities of perspective are not as important to the discourse as the manner in which the technique affects an individual's viewing experience. In Giotto's works, the body was given meaning. Clothing functioned as an allusion to the nakedness of figures, giving flesh to characters in religious narratives. Divine images were no longer mere representations and also drew the audience into commune with their framed realities, opening up questions about truth and beauty among others.